In the intricate landscape of modern electronics, one component stands as a true foundational pillar: the transistor. At its simplest, a transistor is a semiconductor device used to amplify or switch electronic signals and electrical power. These tiny components serve as the fundamental building blocks in everything from the simplest radio to the most powerful supercomputer, making them one of the most significant inventions of the 20th century. Without transistors, the technological revolution that has brought us smartphones, computers, medical equipment, and global communication networks would simply not exist.

A transistor is fundamentally a solid-state semiconductor device with at least three terminals that can amplify a signal or open and close a circuit. In more practical terms, imagine a transistor as an electronically controlled switch or a valve for electrical current. Just as a small force can adjust a water valve to control a powerful flow of water, a tiny electrical signal at one terminal of a transistor can control a much larger current flowing through the other two terminals. This simple yet powerful principle enables the complex functionality found in all modern electronics.

Transistors are designed to perform two primary functions in electronic circuits: amplification and switching. As an amplifier, a transistor takes a weak input signal and produces a stronger output signal, faithfully replicating the pattern of the original signal but at a higher power level. This is crucial in devices like hearing aids, radios, and wireless communication systems where faint signals must be boosted for processing or playback through speakers. As a switch, a transistor can toggle between an “on” state (allowing current to flow) and an “off” state (stopping current flow) millions or even billions of times per second, forming the binary foundation of digital computing where “on” represents 1 and “off” represents 0.

The versatility of transistors extends beyond these core functions, enabling them to serve various essential roles in circuit design, including:

- Voltage regulation: Stabilizing power supply voltages for sensitive components

- Signal modulation: Encoding information onto carrier waves for transmission

- Oscillation: Generating precise frequency signals for timing and communication

- Logic gating: Implementing Boolean logic operations for digital computation

- Current control: Precisely limiting or directing current flow in circuits

History of the Transistor

The transistor was born from decades of scientific inquiry into the properties of semiconductor materials. The first practical device was invented in 1947 at Bell Telephone Laboratories by physicists John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley. Their breakthrough device, known as a point-contact transistor, earned them the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics and marked the dawn of a new electronic age. This invention emerged from research seeking a solid-state replacement for the bulky, fragile, and power-hungry vacuum tubes that had previously been used to amplify and switch signals in electronic equipment.

The transition from vacuum tubes to transistors was revolutionary. Early transistors were initially made from germanium, but this material had significant limitations, including performance breakdown at temperatures around 80°C. This led to a shift toward silicon, which could withstand heat up to approximately 180°C, offering greater reliability and practicality for a wider range of applications. The following timeline highlights key milestones in the early development of transistor technology:

- 1947: Bardeen, Brattain, and Shockley demonstrate the first working point-contact transistor at Bell Labs.

- 1951: Bell Labs announces the first working bipolar NPN junction transistor.

- 1954: The first commercial silicon transistor is produced by Texas Instruments, heralding the shift from germanium to silicon.

- 1955: The first all-transistor car radio is developed by Chrysler and Philco.

- 1957: Sony’s TR-63 transistor radio becomes the first mass-produced device of its kind, catalyzing the widespread adoption of transistor technology in consumer electronics.

How Does a Transistor Work?

To understand how a transistor works, it’s helpful to examine the Bipolar Junction Transistor (BJT), one of the earliest and most fundamental transistor types. A BJT consists of three semiconductor regions: the emitter, the base, and the collector, forming either an NPN or PNP sandwich structure. In this configuration, the base acts as the control terminal that regulates the flow of current between the emitter and collector. When a small current is applied to the base, it enables a much larger current to flow from the collector to the emitter, thus allowing a small signal to control a much larger one.

The operation of a BJT relies on the manipulation of charge carriers within the semiconductor material. In an NPN transistor, when a forward voltage of approximately 0.7 volts or more is applied to the base relative to the emitter, electrons from the emitter flow into the base. Because the base is deliberately made very thin, most of these electrons do not recombine but instead diffuse across to the collector, where they are swept away by the collector voltage, creating a much larger collector current. The ratio of collector current to base current is known as the current gain (hFE), which can range from tens to hundreds, illustrating the transistor’s amplification capability.

While BJTs are current-controlled devices, another major transistor category operates on a different principle. Field-Effect Transistors (FETs), including the widely used MOSFET, are voltage-controlled devices that utilize an electric field to regulate current flow. Instead of a base terminal, FETs have a gate terminal that, when a voltage is applied, creates an electric field that opens or closes a conductive channel between the source and drain terminals. This voltage-control mechanism requires negligible current to maintain the transistor’s state, making FETs particularly valuable for low-power applications and enabling the ultra-dense integration found in modern computer chips.

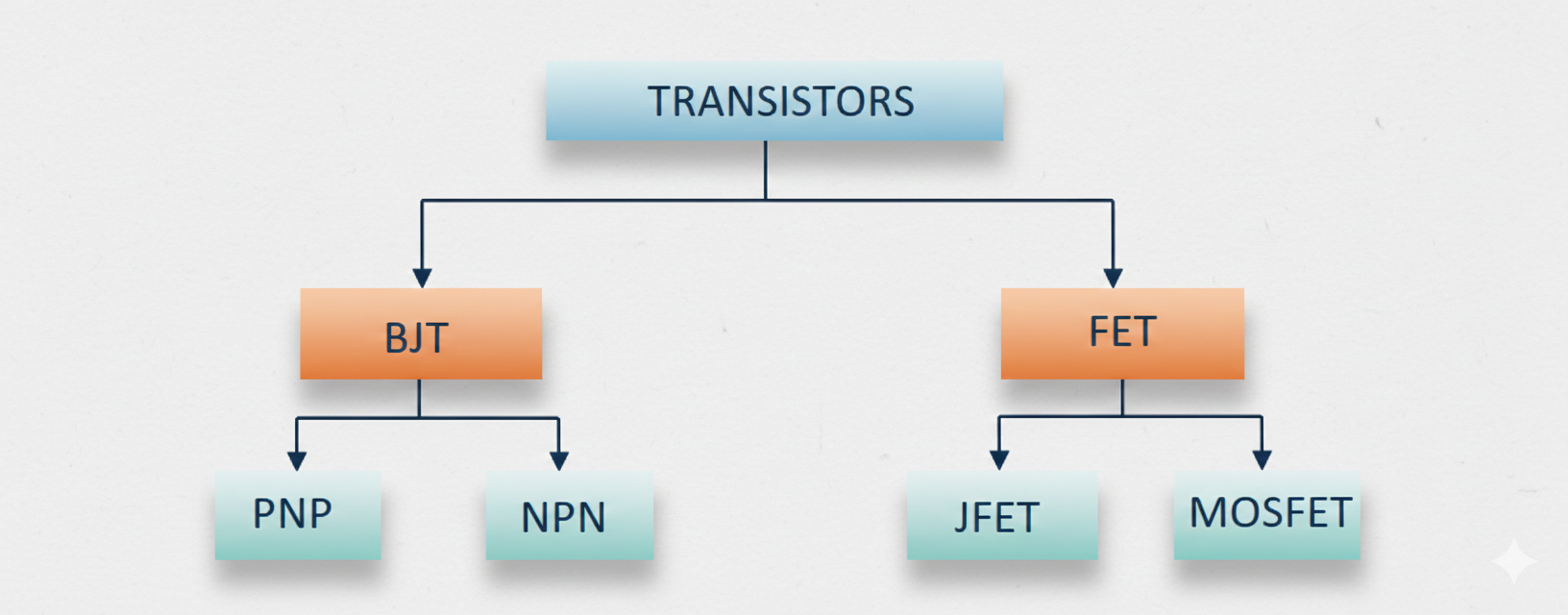

Types of Transistors

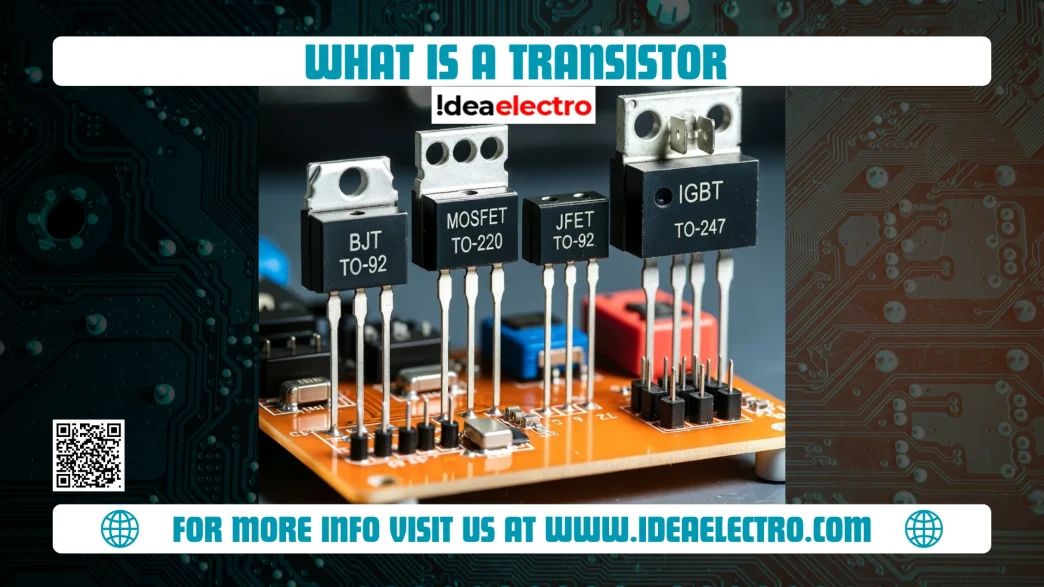

The transistor family has diversified significantly since its invention, with different types optimized for specific applications and performance characteristics. These variants can be broadly categorized into bipolar transistors and field-effect transistors, each with distinct operating principles and advantages. Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJTs), as previously described, are current-controlled devices where a small base current regulates a larger collector-emitter current, making them well-suited for analog amplification applications where linearity and high gain are important.

Field-Effect Transistors (FETs) represent the other major transistor classification and have become the dominant type in digital integrated circuits due to their superior power efficiency and scalability. The Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor FET (MOSFET) is particularly important, as it forms the foundation of most modern microprocessors and memory chips. Unlike BJTs, MOSFETs are voltage-controlled devices that draw negligible gate current in steady-state operation, which significantly reduces their static power consumption. Other FET variants include the Junction FET (JFET) and the Metal-Semiconductor FET (MESFET), each with specialized applications in high-frequency and analog circuits.

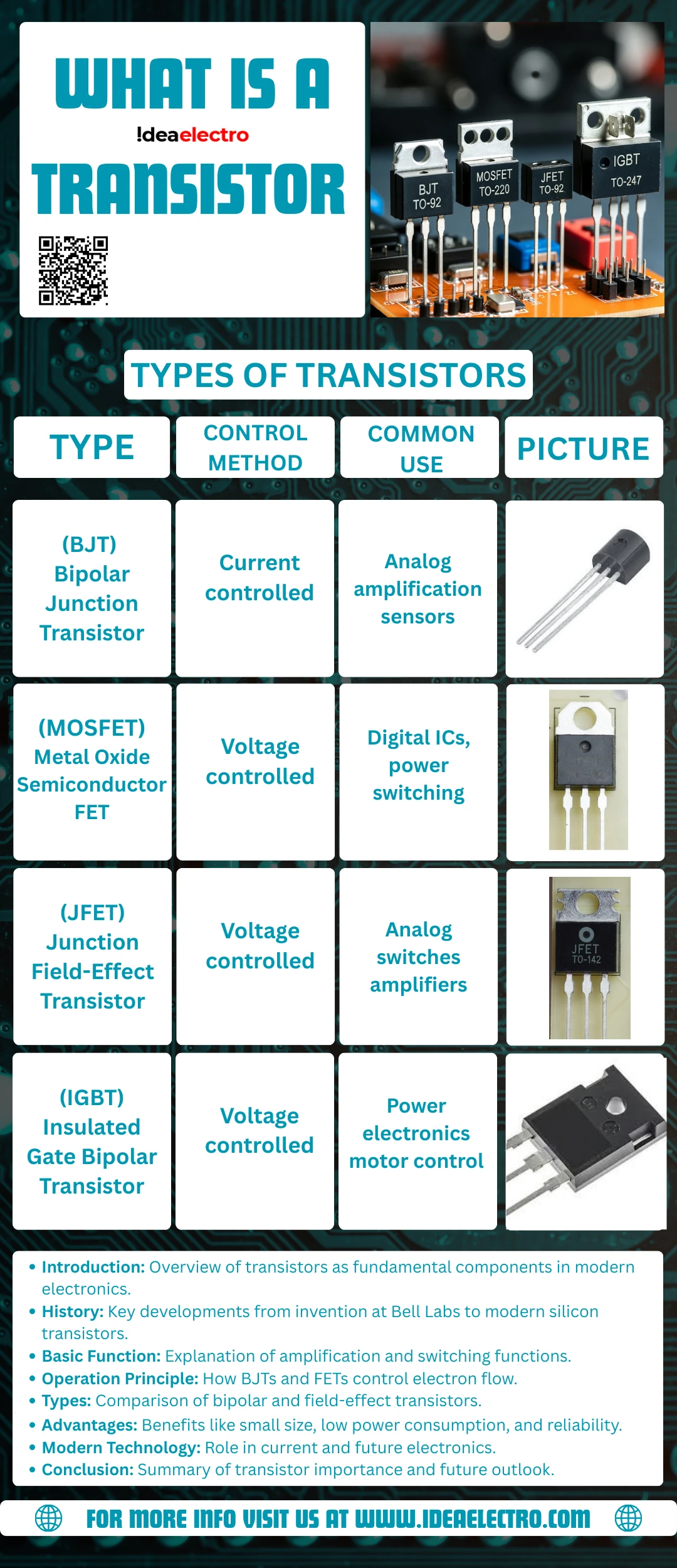

Table: Comparison of Major Transistor Types

| Type | Control Method | Common Use | Power Efficiency |

| BJT (Bipolar Junction Transistor) | Current-controlled | Analog amplification, sensors | Moderate |

| MOSFET (Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor FET) | Voltage-controlled | Digital ICs, power switching | High |

| JFET (Junction Field-Effect Transistor) | Voltage-controlled | Analog switches, amplifiers | High |

| IGBT (Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistor) | Voltage-controlled | Power electronics, motor control | High for high-power applications |

Beyond these fundamental types, several specialized transistors have been developed to address specific needs. The Insulated-Gate Bipolar Transistor (IGBT) combines the easy drive characteristics of a MOSFET with the high-current handling capability of a BJT, making it ideal for high-power applications like motor drives and power inverters. Other specialized variants include high-electron-mobility transistors (HEMTs) for high-frequency applications and radiation-hardened transistors designed for space and military applications where reliability under extreme conditions is paramount.

Uses and Applications of Transistors

The practical applications of transistors are virtually limitless, spanning nearly every electronic device imaginable. In their role as switches, transistors form the foundational element of digital logic circuits, microprocessors, and memory chips that power computers, smartphones, and countless other digital devices. A modern CPU may contain billions of nanoscale transistors, each switching on and off billions of times per second to perform calculations, process data, and execute instructions. The remarkable reliability of these transistors is evidenced by the fact that they can theoretically switch continuously at high frequencies for millions of years without a single error.

As amplifiers, transistors are indispensable in audio systems, radio communications, and sensor interfaces. In a radio receiver, for instance, transistors amplify the extremely weak signals intercepted by the antenna, boosting them to levels sufficient to drive speakers. Similarly, in medical devices like hearing aids, transistors amplify faint sound signals to assist people with hearing impairment. Beyond these core functions, transistors serve critical roles in power regulation circuits, where they help maintain stable voltage levels despite fluctuations in load current or input voltage, ensuring the proper operation of sensitive electronic components.

The application spectrum of transistors continues to expand into new domains, including:

- Internet of Things (IoT): Low-power transistors enable smart sensors, connected devices, and edge computing systems that form the IoT ecosystem

- Renewable energy systems: Power transistors facilitate efficient conversion and management of solar and wind energy

- Electric vehicles: High-power transistors control motor drives and manage battery systems in transportation electrification

- Medical technology: Miniaturized transistors enable implantable devices, diagnostic equipment, and health monitoring systems

- Artificial intelligence: Specialized transistors optimized for neural network computations accelerate machine learning workloads

Advantages of Transistors

The revolutionary impact of transistors stems from their compelling advantages over previous technologies, particularly vacuum tubes. First and foremost, their small size has enabled the dramatic miniaturization of electronic devices, with modern transistors measuring just nanometers in scale. This compactness allows billions of transistors to be integrated onto a single silicon chip, creating the powerful microprocessors that drive today’s computational capabilities. The ongoing reduction in transistor dimensions has consistently followed the trend described by Moore’s Law, roughly doubling the number of transistors per chip every two years.

Another decisive advantage is their low power consumption. Compared to vacuum tubes that required heated filaments consuming substantial power, transistors operate as solid-state devices with no heating elements, dramatically reducing their energy requirements. As transistors shrink further, they can operate at lower voltages, providing additional power savings—a critical consideration for battery-powered portable devices. The power efficiency of transistors stems partly from reduced parasitic capacitances in smaller devices and the square-law relationship between dynamic power consumption and operating voltage (P ∝ CV²f), where lowering voltage yields dramatic power reductions.

Additional significant advantages include:

- High reliability and longevity: With no fragile glass envelopes or heated filaments, transistors boast much longer operational lifetimes than vacuum tubes

- Fast switching speeds: Modern transistors can switch between states in picoseconds, enabling the gigahertz clock frequencies of contemporary processors

- Mechanical robustness: Their solid-state construction makes transistors resistant to shock, vibration, and physical trauma

- Manufacturing scalability: Semiconductor fabrication processes allow mass production of transistors at infinitesimal scales and minimal cost per device

Transistors in Modern Technology

In our contemporary technological landscape, transistors continue to be the workhorse components that enable innovation across multiple domains. The proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, which is expected to reach 29 billion units by 2030, relies heavily on low-power transistors that can operate for extended periods on limited power sources. Similarly, the expansion of 5G connectivity and the ongoing research into 6G technologies demand transistors capable of operating at extremely high frequencies with minimal power consumption, pushing the boundaries of semiconductor technology.

At the frontier of transistor development, researchers are exploring novel approaches to overcome the fundamental physical limits of conventional silicon transistors. Scientists at MIT have developed nanoscale transistors using ultrathin semiconductor materials like gallium antimonide and indium arsenide, creating vertical nanowire transistors just a few nanometers wide. These devices leverage quantum tunneling—where electrons penetrate through energy barriers rather than going over them—to operate efficiently at much lower voltages than conventional transistors, potentially revolutionizing energy efficiency in future electronics.

Other promising research directions include:

- Magnetic transistors: MIT engineers have recently demonstrated a transistor that replaces silicon with a magnetic semiconductor (chromium sulfur bromide), enabling more energy-efficient operation with built-in memory functionality

- Specialized AI chips: The development of application-specific transistors optimized for neural network computations to accelerate artificial intelligence workloads

- 3D integration: Stacking transistor layers vertically rather than spreading them horizontally to continue performance scaling beyond planar limitations

- Novel semiconductor materials: Exploration of graphene, carbon nanotubes, and other two-dimensional materials as potential successors to silicon

Conclusion

From their humble beginnings as a laboratory curiosity at Bell Labs in 1947, transistors have evolved to become the indispensable enablers of our digital world. These remarkable semiconductor devices, through their dual capabilities of signal amplification and electronic switching, form the foundational infrastructure upon which all modern electronics is built. The continuous innovation in transistor technology—from the first germanium point-contact devices to today’s nanoscale silicon MOSFETs and emerging quantum tunneling transistors—has consistently pushed the boundaries of what is electronically possible, driving progress across computing, communications, medicine, and countless other fields.

As we look toward the future, the importance of transistors shows no sign of diminishing. While the classical silicon transistor may eventually approach fundamental physical limits, ongoing research into magnetic semiconductors, quantum tunneling devices, and novel materials promises to extend the trajectory of progress well into the future. The incredible journey of the transistor—from a macroscopic laboratory apparatus to nanoscale components smaller than a virus—stands as a testament to human ingenuity and remains one of technology’s most transformative narratives, quietly powering the modern world one switch at a time.