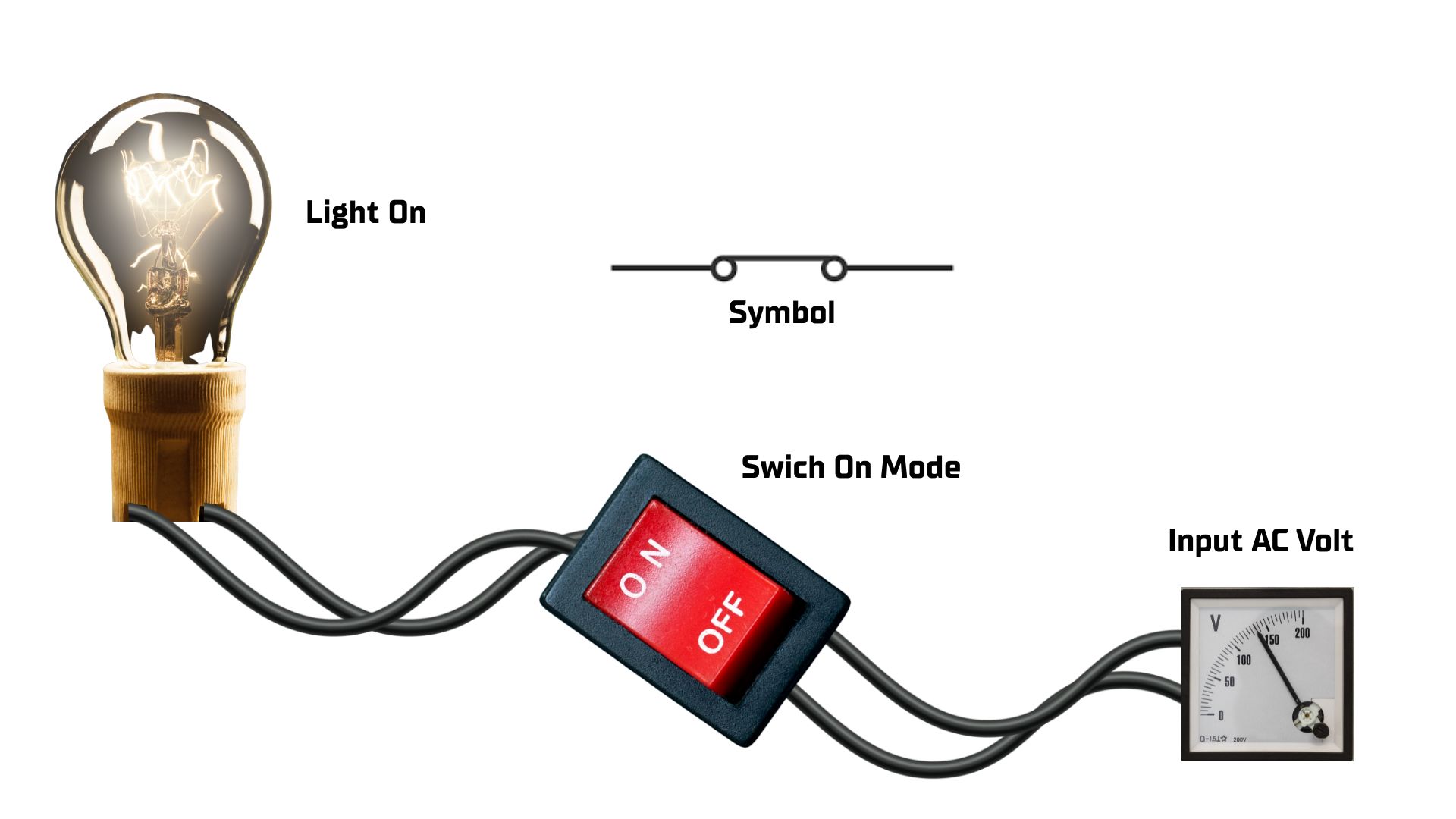

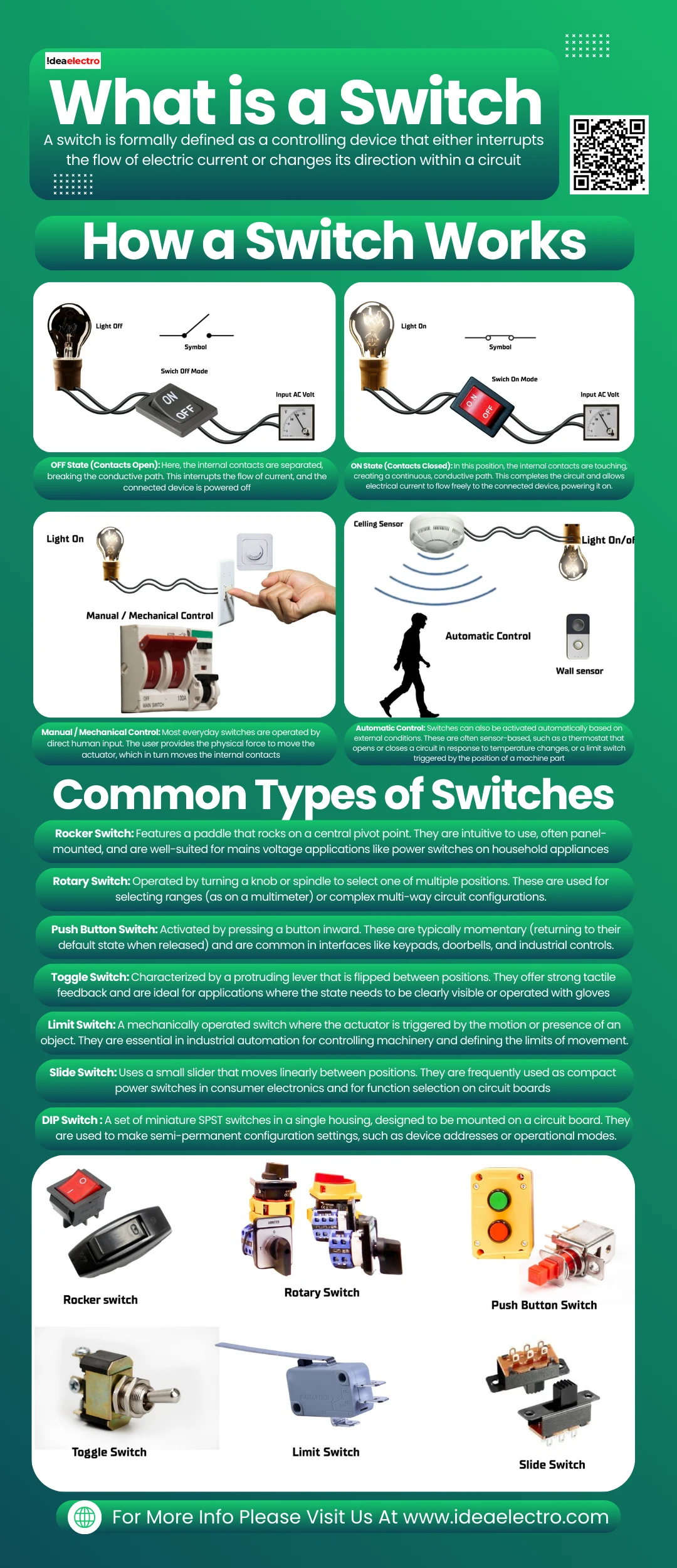

A switch is formally defined as a controlling device that either interrupts the flow of electric current or changes its direction within a circuit. This can be performed either automatically or manually. The basic working principle is elegantly simple: a switch operates by either completing a path for electricity to flow (turning a circuit “ON”) or breaking that path (turning it “OFF”). Internally, this is achieved through movable conductive contacts that connect to or disconnect from stationary terminals. When these contacts touch, the circuit is closed, and current flows; when they are separated, the circuit is open, and the flow stops. This fundamental make-or-break operation is the universal principle behind all switching actions, regardless of the switch’s complexity or size.

How a Switch Works

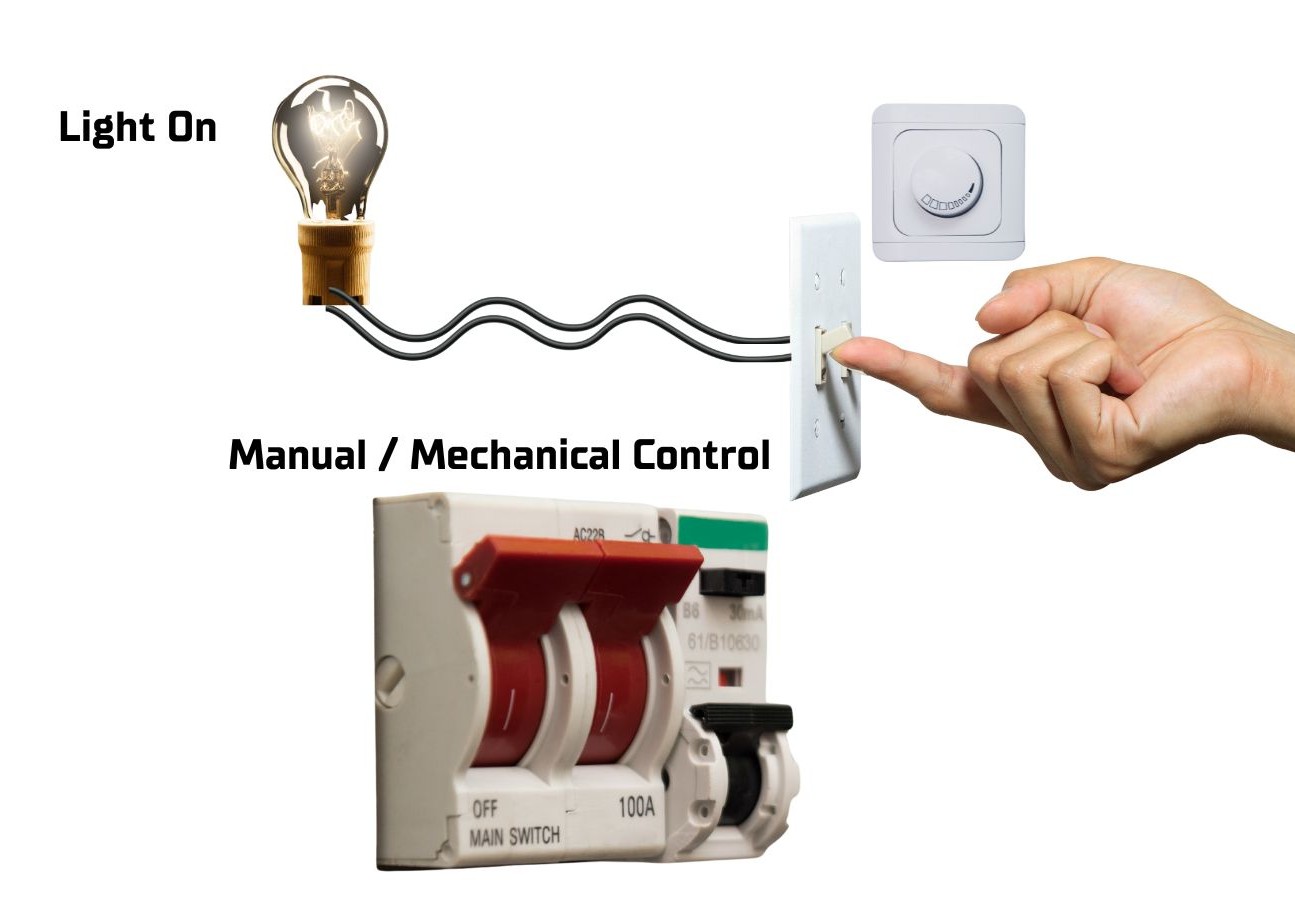

The internal mechanism of a basic mechanical switch revolves around the movement of metal contacts. These contacts are physically opened or closed by an actuator—such as a lever, button, or rocker—that is manipulated by the user. Inside the switch housing, an armature attached to the actuator moves to place an electrical contact into a circuit or remove it. Many switches provide tactile and audible feedback, like a click, to confirm the state change through physical resistance from an internal spring mechanism.

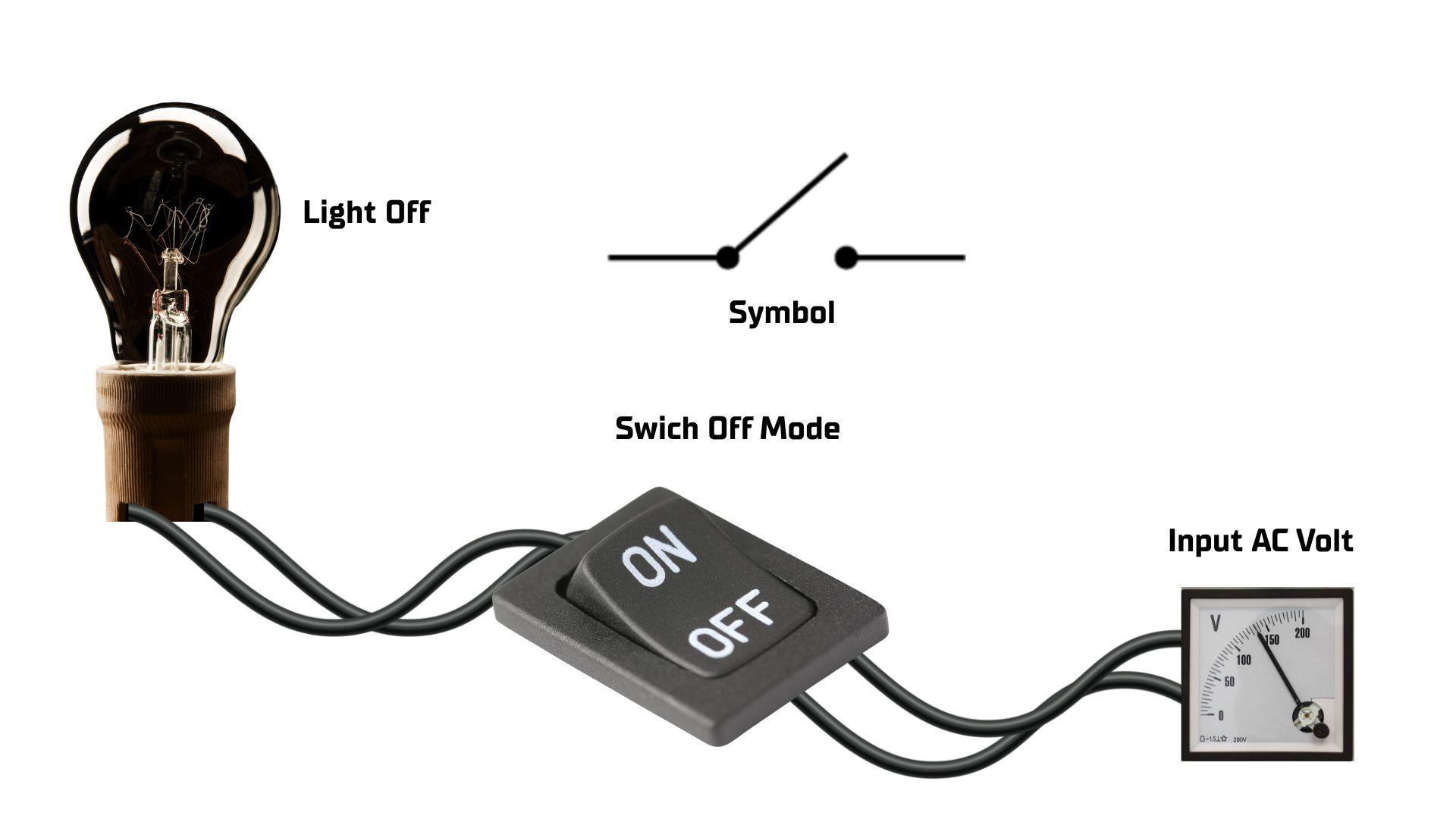

- ON State (Contacts Closed):In this position, the internal contacts are touching, creating a continuous, conductive path. This completes the circuit and allows electrical current to flow freely to the connected device, powering it on.

- OFF State (Contacts Open):Here, the internal contacts are separated, breaking the conductive path. This interrupts the flow of current, and the connected device is powered off.

- Manual / Mechanical Control:Most everyday switches are operated by direct human input. The user provides the physical force to move the actuator, which in turn moves the internal contacts.

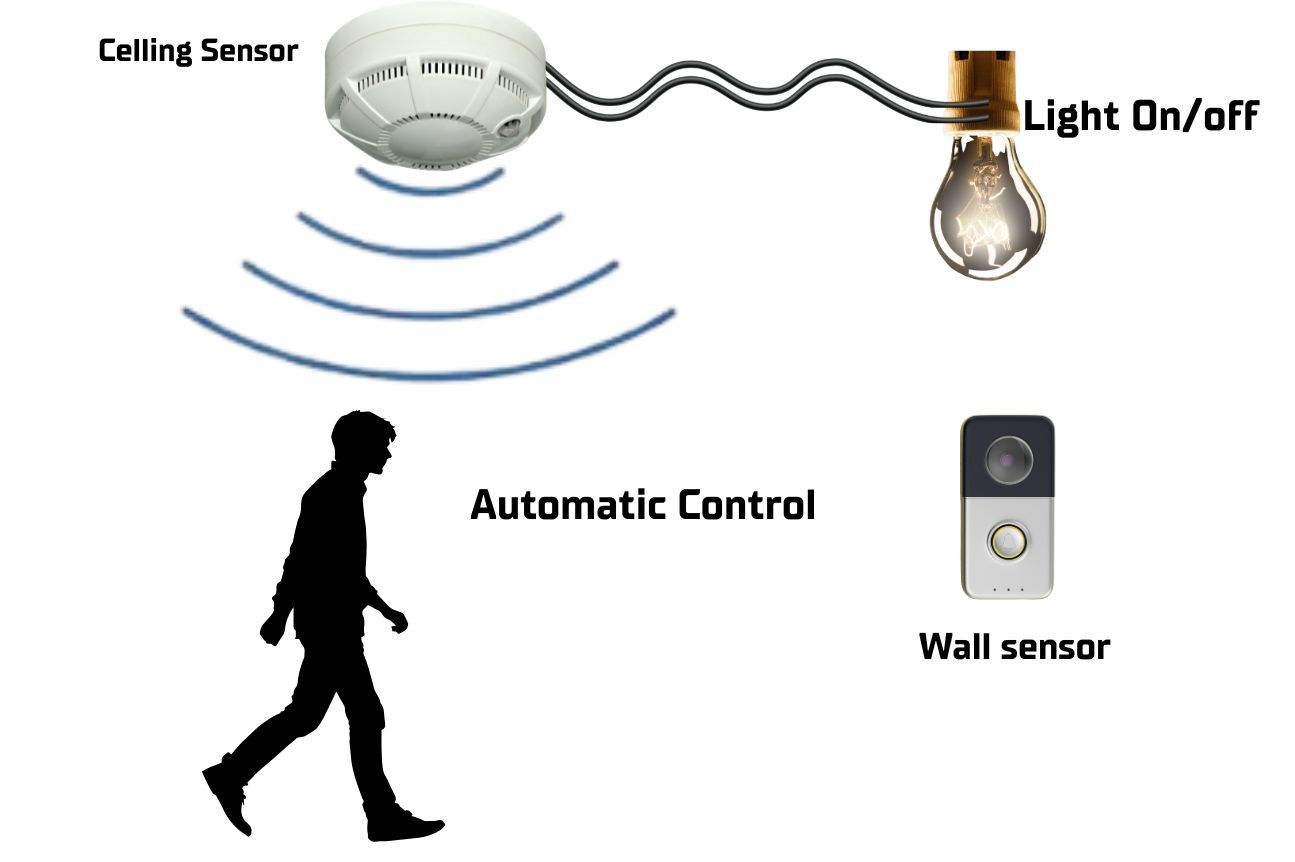

- Automatic Control:Switches can also be activated automatically based on external conditions. These are often sensor-based, such as a thermostat that opens or closes a circuit in response to temperature changes, or a limit switch triggered by the position of a machine part.

Common Types of Switches

Switches come in a wide variety of forms, each designed for specific applications and user interfaces. The selection is vast, ranging from subminiature components to large industrial units, with choices often driven by required functionality, environmental conditions, and aesthetic design.

- Toggle Switch:Characterized by a protruding lever that is flipped between positions. They offer strong tactile feedback and are ideal for applications where the state needs to be clearly visible or operated with gloves.

- Push Button Switch:Activated by pressing a button inward. These are typically momentary (returning to their default state when released) and are common in interfaces like keypads, doorbells, and industrial controls.

- Rocker Switch:Features a paddle that rocks on a central pivot point. They are intuitive to use, often panel-mounted, and are well-suited for mains voltage applications like power switches on household appliances.

- Slide Switch:Uses a small slider that moves linearly between positions. They are frequently used as compact power switches in consumer electronics and for function selection on circuit boards.

- Rotary Switch:Operated by turning a knob or spindle to select one of multiple positions. These are used for selecting ranges (as on a multimeter) or complex multi-way circuit configurations.

- Limit Switch:A mechanically operated switch where the actuator is triggered by the motion or presence of an object. They are essential in industrial automation for controlling machinery and defining the limits of movement.

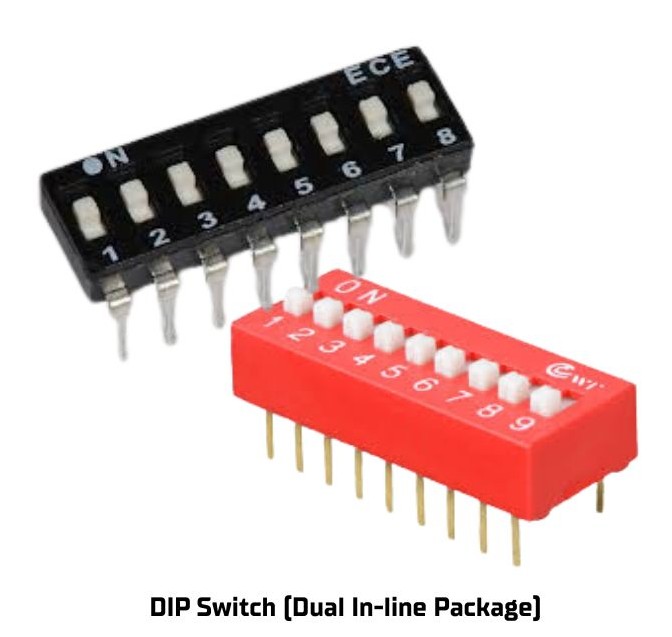

- DIP Switch (Dual In-line Package):A set of miniature SPST switches in a single housing, designed to be mounted on a circuit board. They are used to make semi-permanent configuration settings, such as device addresses or operational modes.

Switch Pole and Throw Configuration

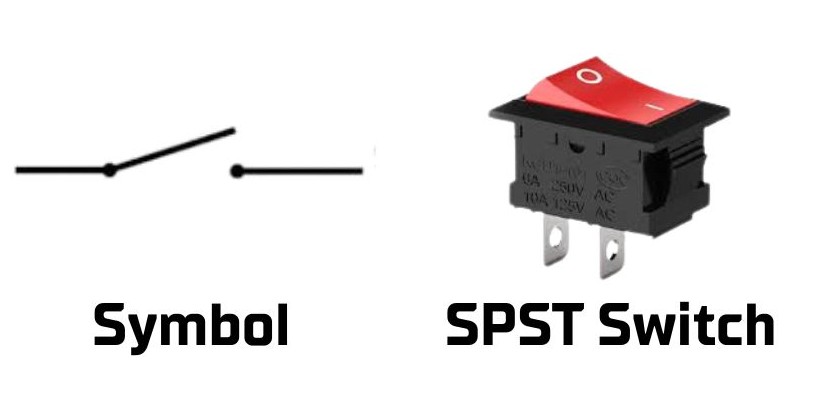

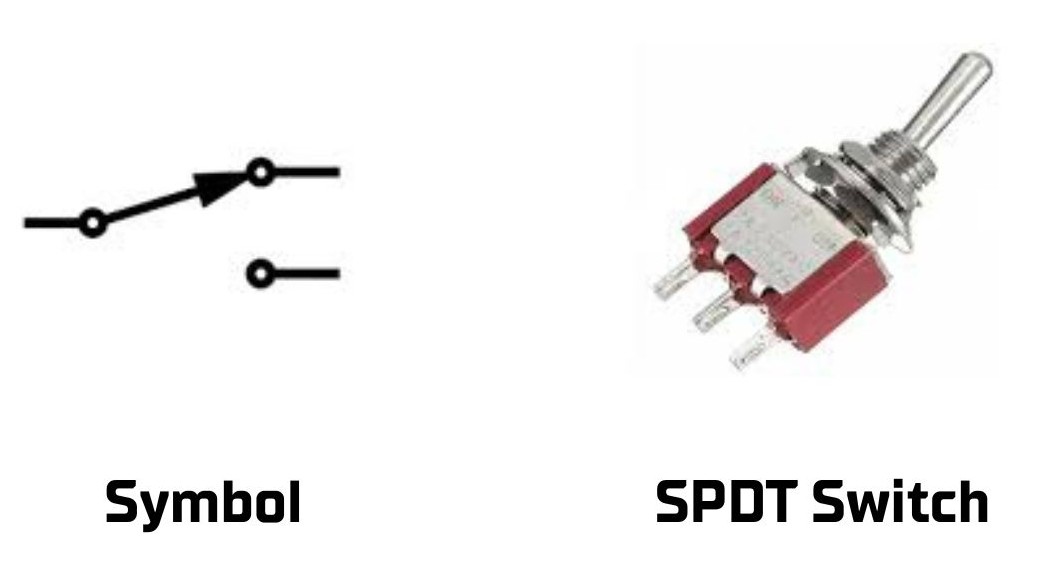

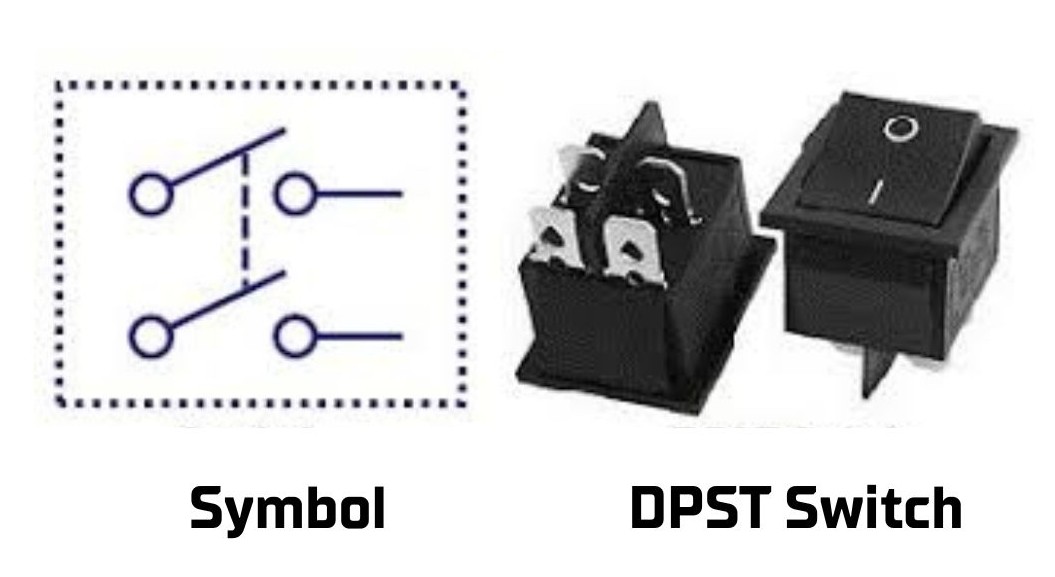

To understand a switch’s capability, one must understand its “pole” and “throw” configuration. These terms define how many circuits a switch can control and how many paths each circuit can take. A pole refers to the number of separate input circuits controlled by a single actuator. A throw refers to the number of output connections to which each pole can be connected. Common configurations are summarized in the table below:

| Configuration | Full Form | Key Description |

| SPST | Single Pole, Single Throw |

The simplest switch. Controls one circuit with a simple ON/OFF action. |

| SPDT | Single Pole, Double Throw |

One input can connect to one of two different outputs. Often used as a changeover or selector switch. |

| DPST | Double Pole, Single Throw |

Controls two completely separate circuits simultaneously with one ON/OFF action. |

| DPDT | Double Pole, Double Throw |  Controls two independent circuits, with each having two possible output paths. Offers the highest flexibility among common types. Controls two independent circuits, with each having two possible output paths. Offers the highest flexibility among common types. |

The pole and throw configuration directly dictates the switching flexibility. A higher number of poles allows a single switch to control more circuits at once, which is crucial for safety in AC power systems where both live and neutral lines must be broken. More throws provide more path options for the current, enabling functions like motor reversal or input source selection. This systematic rating structure ensures switches are applied correctly according to the demands of the circuit they control.

Applications of Switches

Switches are essential because they provide the primary point of control and safety isolation in virtually every electrical system. Their applications span all sectors of technology and daily life.

- Home Electrical Systems:Light switches, dimmers, appliance controls, and circuit breakers are all forms of switches that manage power and lighting throughout a home.

- Industrial Machinery:Heavy-duty switches, including limit switches, push buttons, and selector switches, are used to control motors, conveyor systems, and automated processes, often in harsh environments.

- Electronics and Gadgets:Miniature and subminiature switches like tactiles, slides, and DIP switches are embedded in computers, smartphones, remote controls, and other portable devices for user input and configuration.

- Automotive Systems:From ignition switches and turn signals to power window controls and dashboard toggles, switches are integral to vehicle operation and user interfaces.

- Telecommunication Devices:Switches route signals in networking equipment, and keypads (arrays of push-button switches) are used for dialing and control.

- Power Control and Automation:At the highest levels, high-voltage circuit breakers (a specialized form of switch) protect electrical grids, and relays (electrically operated switches) form the basis of automation and control logic.

Advantages of Using Switches

The widespread use of switches is driven by several key benefits:

- Easy Circuit Control:They provide a simple, intuitive interface for users to operate complex electrical systems.

- Safety:Switches allow for the safe isolation of circuits from power sources for maintenance and protect systems from overloads when used as breakers.

- Low Cost and Reliability:Simple mechanical switches are inexpensive to manufacture and, when used within their ratings, offer extremely reliable performance over thousands of cycles.

- Versatility:Available in countless forms, sizes, and configurations, a suitable switch can be found for almost any conceivable application, from low-voltage signal routing to high-power distribution.

Choosing the Right Switch

Selecting the appropriate switch requires matching its specifications to the demands of the application. Key factors to consider include:

- Electrical Ratings:The switch must be rated for both the maximum voltage and current (amperage) of the circuit. Exceeding these ratings can cause overheating, arcing, and failure.

- Environmental Factors:Consider the operating environment. Will the switch be exposed to dust, moisture, extreme temperatures, or vibration? Ingress Protection (IP) ratings define a switch’s resistance to dust and water, which is critical for outdoor or industrial use.

- Type of Operation:Determine if a maintained (stays in position) or momentary (returns when released) action is needed. Also, consider the required actuator style (toggle, button, etc.) for usability.

- Durability (Lifecycle):The switch should have a mechanical life (number of on/off cycles) that exceeds the expected use of the product.

- Size and Mounting Style:The switch must fit the physical design, whether it needs to be panel-mounted, soldered to a PCB (through-hole or surface-mount), or attached to a DIN rail.

Conclusion

In summary, the switch is a deceptively simple component that performs the vital function of controlling electrical flow, forming the essential link between user intent and system operation. Its importance extends from providing basic convenience and functionality to ensuring critical safety in complex systems. A solid understanding of switch types, configurations, and selection criteria is fundamental for anyone involved in designing, building, or maintaining electrical and electronic systems. By making or breaking circuits with reliability and precision, switches remain an indispensable pillar of electrical engineering and modern technology.