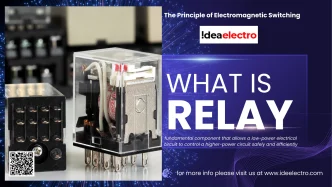

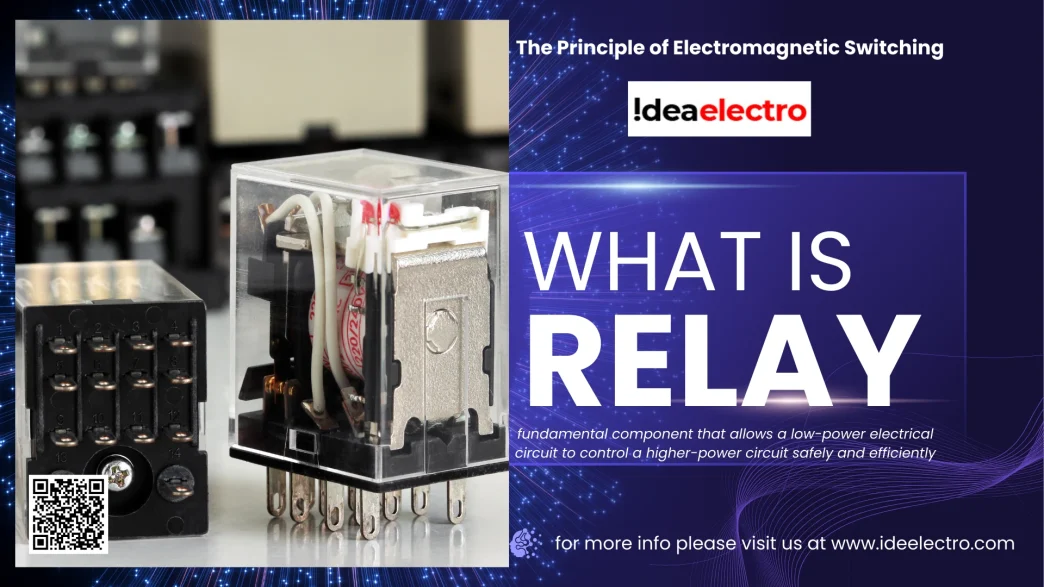

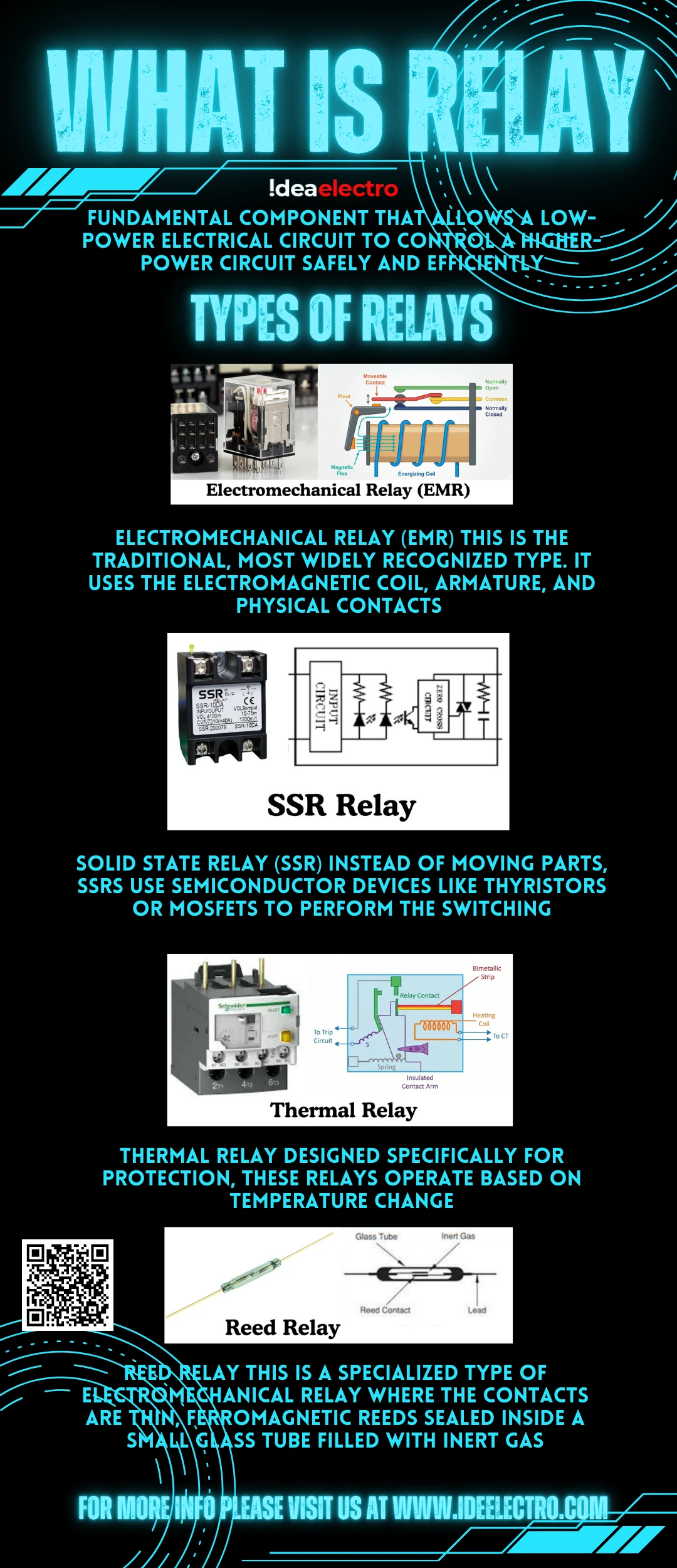

A relay is an electrically operated switch. It is a fundamental component that allows a low-power electrical circuit to control a higher-power circuit safely and efficiently. By receiving a small electrical signal, a relay can open or close contacts to turn another device on or off, functioning much like a runner in a race passing a baton. This simple yet powerful ability to isolate control signals from power circuits makes relays indispensable across countless applications, from industrial machinery and automotive systems to everyday home appliances. Their role in enabling remote and automatic control of electrical systems is a cornerstone of modern automation and protection schemes.

How a Relay Works: The Principle of Electromagnetic Switching

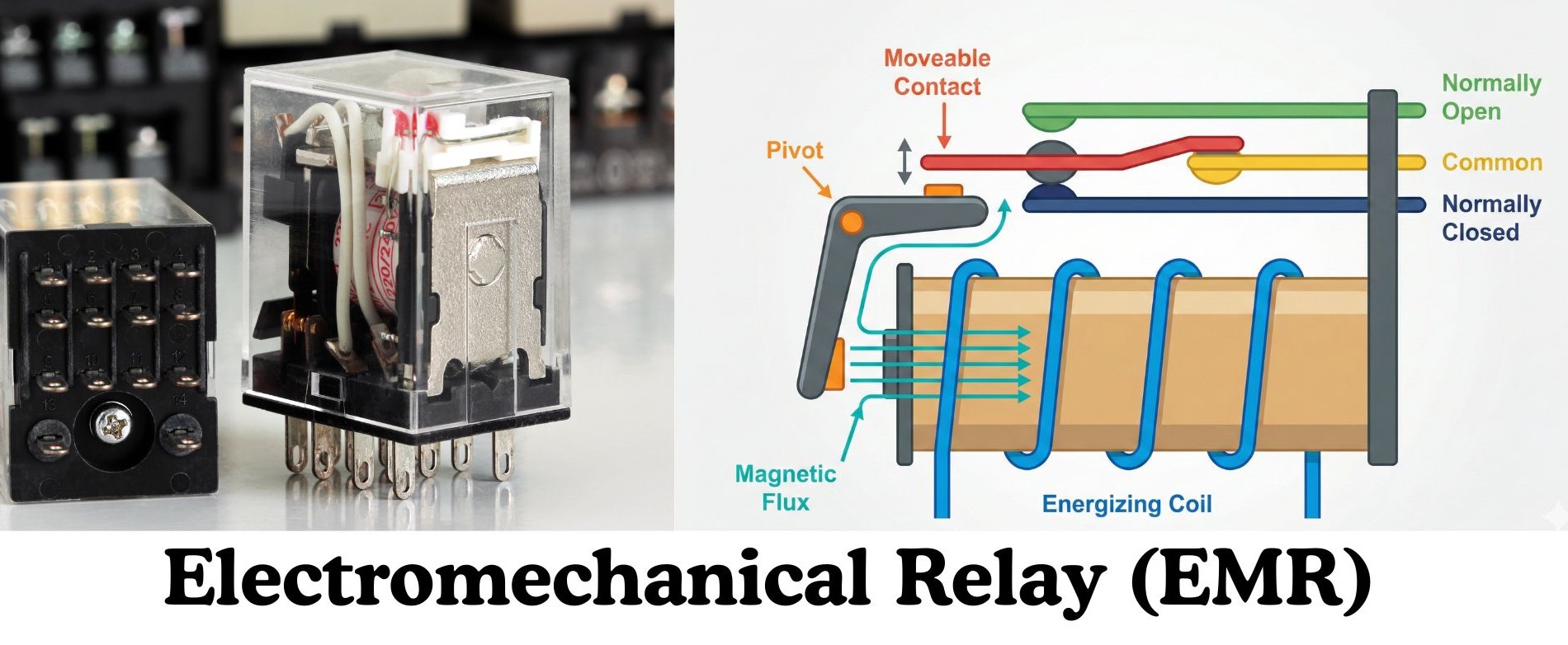

At its core, the most common type of relay operates on the principle of electromagnetic induction. Imagine a relay as having two completely separate circuits: a low-voltage control circuit and a high-voltage load circuit. The control circuit is connected to a coil of wire wound around an iron core. When a small current flow through this coil, it generates a magnetic field. This magnetic field attracts a movable metal component called an armature, which is mechanically linked to one or more electrical contacts in the load circuit. The movement of this armature either opens or closes these contacts, thereby switching the high-power load circuit on or off. When the control current is switched off, the magnetic field collapses, and a spring returns the armature to its default position. This elegant mechanism enables a tiny signal from a sensor or microcontroller to safely start a large motor, turn on bright lights, or activate an alarm system.

Types of Relays: Choosing the Right Tool for the Job

Relays are classified based on their operation principle and specific application needs. The four most common categories are:

- Electromechanical Relay (EMR):This is the traditional, most widely recognized type. It uses the electromagnetic coil, armature, and physical contacts as described above. EMRs are valued for their simplicity, robustness, and ability to handle a wide range of voltages and currents. However, their mechanical nature means they have moving parts that can wear out over time and produce an audible clicking sound.

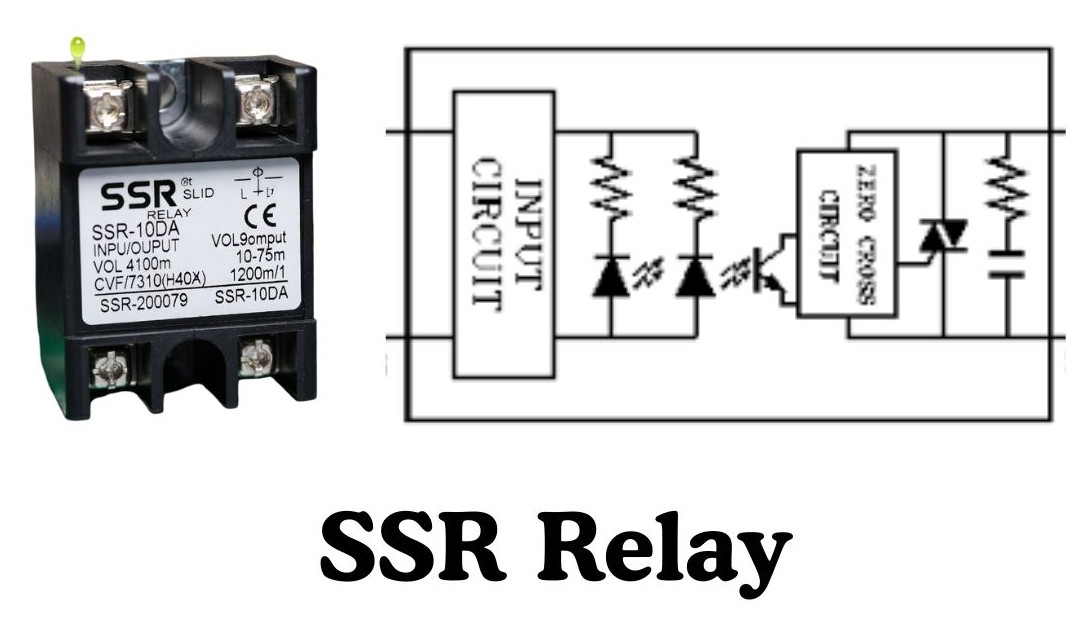

- Solid State Relay (SSR):Instead of moving parts, SSRs use semiconductor devices like thyristors or MOSFETs to perform the switching. An internal light-emitting diode (LED) activates a light-sensitive component to trigger the output. Key advantages include very fast switching speeds, silent operation, and exceptionally long life because there is no contact wear. A trade-off is that they can generate more heat and may have a higher initial cost than EMRs.

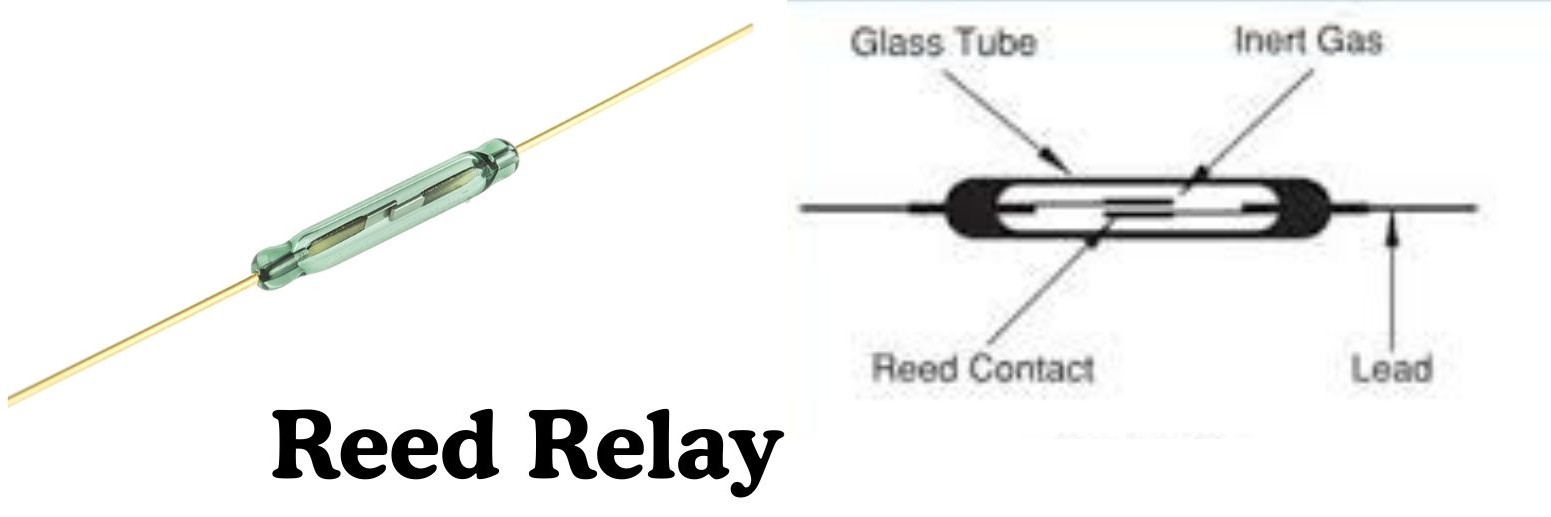

- Reed Relay:This is a specialized type of electromechanical relay where the contacts are thin, ferromagnetic reeds sealed inside a small glass tube filled with inert gas. When the surrounding coil is energized, the reeds magnetically attract each other, closing the contact. Reed relays are known for being very small and fast-acting, making them ideal for switching low-power signals in telecommunications and test equipment.

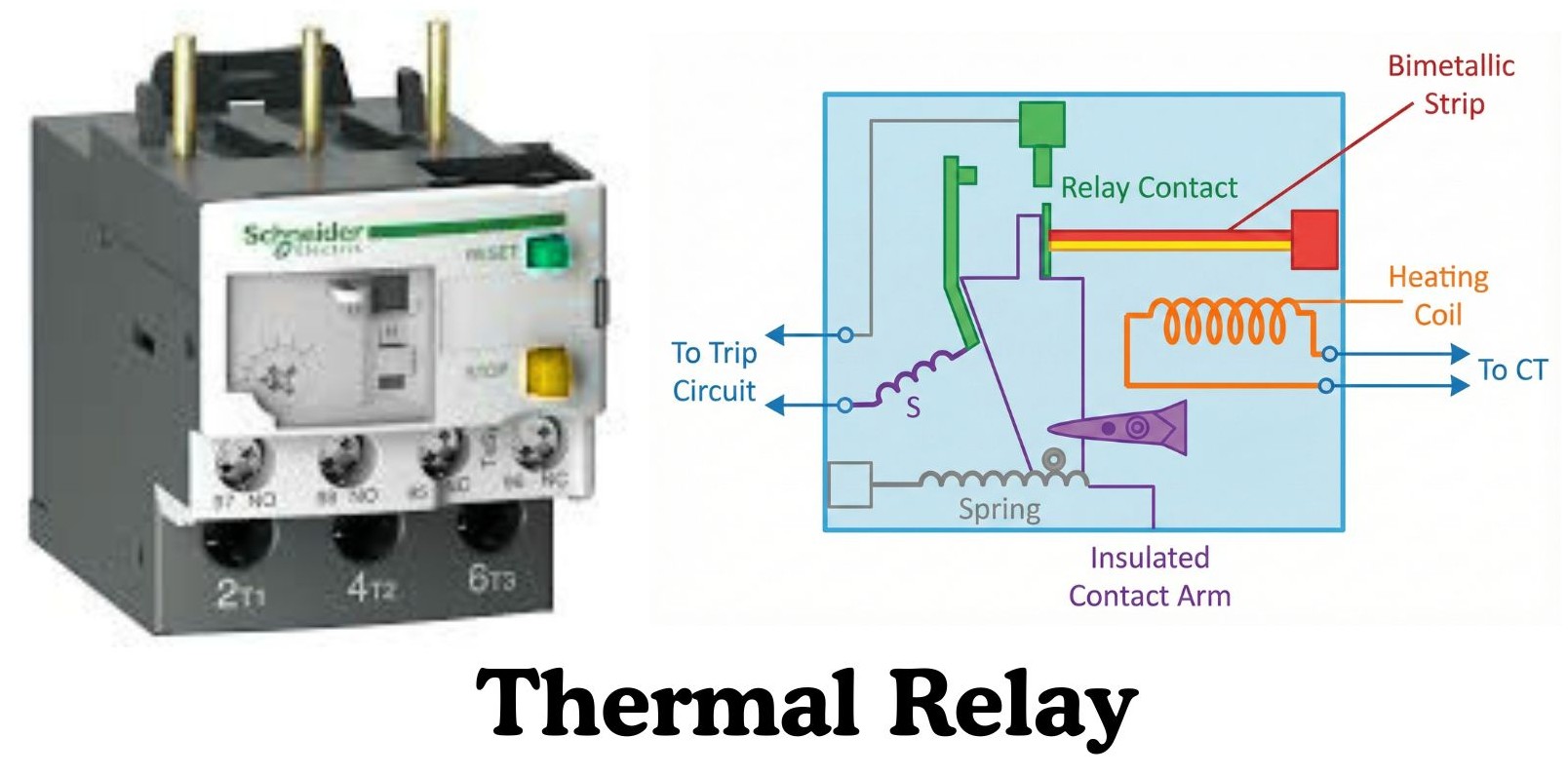

- Thermal Relay:Designed specifically for protection, these relays operate based on temperature change. They often contain a bimetallic strip that bends when heated by an overload current, eventually tripping a switch to cut power. They are commonly used as overload protectors for electric motors.

To fully understand a relay’s function, it helps to break down its physical construction. A standard electromechanical relay consists of four main parts:

- Coil:A wire wound around a metal core. When current flows through it, the coil converts electrical energy into a magnetic field.

- Armature:The movable component, often a hinged or pivoting metal piece. It is attracted by the magnetic field generated by the coil and serves as the common connection for the contacts.

- Contacts:The conductive points that open or close the load circuit. A relay typically has a common (COM) contact connected to the armature, a Normally Open (NO) contact, and a Normally Closed (NC) contact.

- Spring:This ensures the armature returns to its resting position when the coil is de-energized, providing the reset force for the relay.

Ubiquitous Applications in Daily Life and Industry

The ability to control high power with low power and provide electrical isolation makes relays ubiquitous. Common applications span numerous fields:

- Automotive:Relays control high-current devices like headlights, horns, starter motors, and fuel pumps, allowing small switches on the dashboard to manage large electrical loads.

- Home Appliances:They are embedded in washing machines, refrigerators, and air conditioning systems to cycle motors, compressors, and heating elements on and off automatically.

- Industrial Automation:Relays form the backbone of control panels, operating machine tools, conveyor belts, safety alarms, and solenoid valves in factory automation.

- Power Systems and Protection:Specialized protective relays are critical for guarding electrical grids, transformers, and motors by detecting faults like overcurrent, under-voltage, or phase imbalances and isolating the affected equipment.

How to test Relay

Testing a relay is a critical step when troubleshooting electrical circuits, as these components can eventually fail due to mechanical wear or coil burnout. A faulty relay often produces a clicking sound without activating the connected device, or it may remain completely silent when powered. To confirm its condition, you can perform basic diagnostic checks using a digital multimeter to measure coil resistance and verify contact continuity. While these initial readings are helpful, performing a proper diagnosis requires specific techniques to ensure accuracy and safety. For a comprehensive, step-by-step tutorial on the process, read our detailed guide on how to test a relay.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Relays

When selecting a relay for a project, engineers weigh its inherent strengths and limitations. The following table summarizes the key trade-offs, particularly for electromechanical relays.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Control High Power with Low Power: A small coil current can switch a much larger load current. | Mechanical Wear: Moving contacts and armatures degrade over millions of cycles, limiting lifespan. |

| Complete Electrical Isolation: The coil and contact circuits are physically separated, protecting sensitive control electronics. | Slower Switching Speed: Mechanical movement (typically 5-15ms) is slower than solid-state alternatives. |

| Simple and Reliable: Electromechanical designs are robust, easy to understand, and tolerant of voltage surges. | Audible Noise and Arcing: The armature movement creates a click, and contact separation can cause electrical arcing, especially with inductive loads. |

Conclusion

In summary, relays remain a vital and enduring technology in electrical and electronic engineering. Their fundamental role in providing safe isolation, enabling interfacing between low- and high-power circuits, and offering reliable control ensures their continued relevance. While modern solid-state relays excel in speed and longevity for many applications, the simplicity, robustness, and cost-effectiveness of traditional electromechanical relays guarantee they will continue to be the switch of choice in a vast array of systems, from the simplest automotive function to the most complex industrial automation.