In simple terms, a potentiometer is a variable resistor. Unlike a standard fixed resistor, which has one unchangeable resistance value, a potentiometer allows you to manually and continuously adjust its resistance. This is achieved through a mechanical interface, like a turning knob or a sliding fader. The basic principle is that by moving a contact along a resistive track, you effectively change the length of the resistive path the electric current must travel, thereby increasing or decreasing the resistance. This direct relationship between physical position and electrical resistance is what makes potentiometers so versatile for control applications.

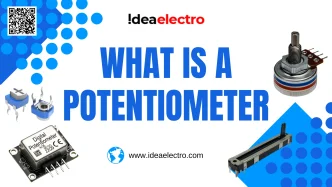

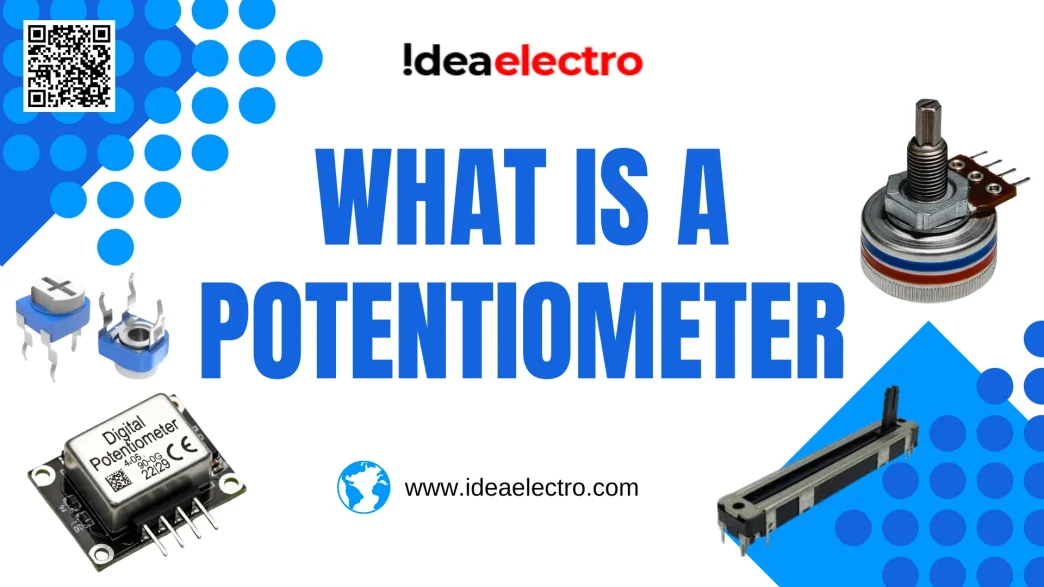

An Essential Component for Control and Measurement in Electronics

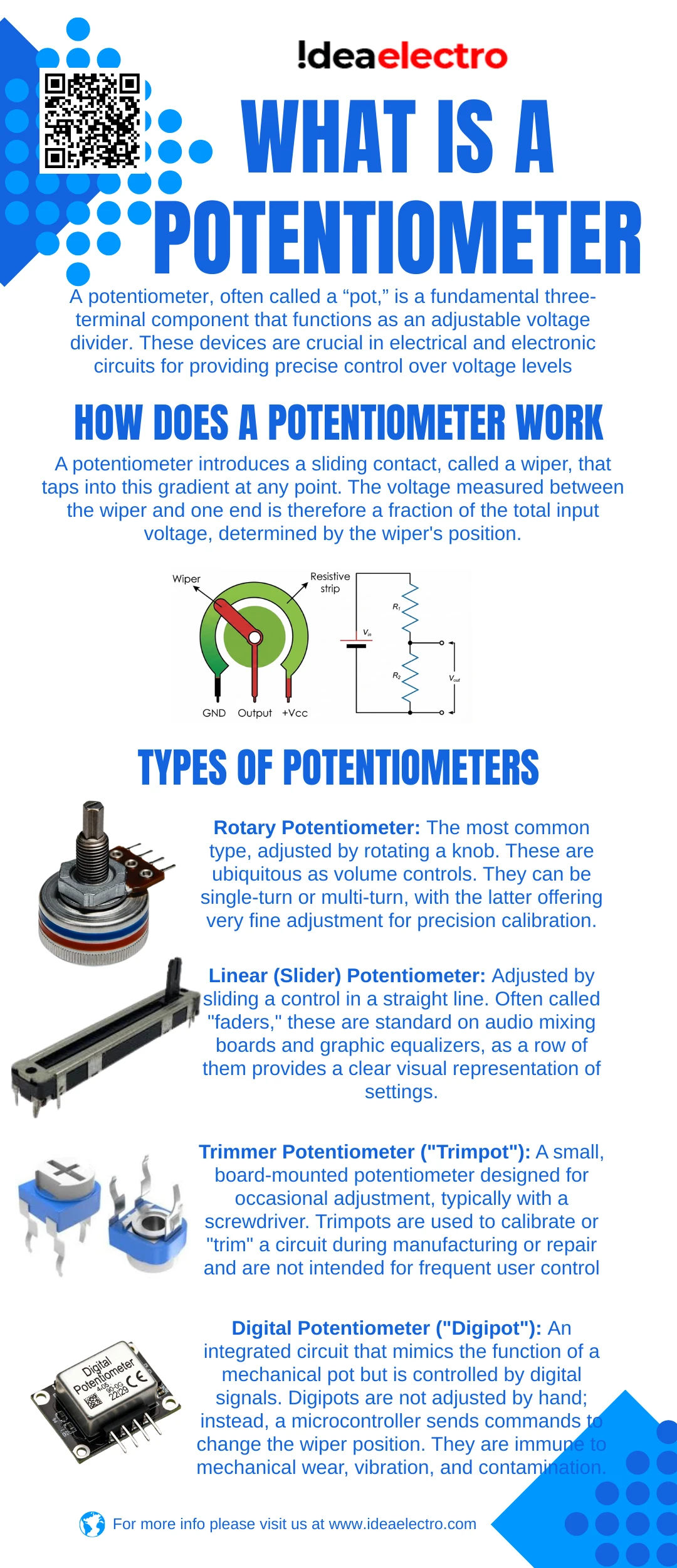

A potentiometer, often called a “pot,” is a fundamental three-terminal component that functions as an adjustable voltage divider. These devices are crucial in electrical and electronic circuits for providing precise control over voltage levels, which in turn regulates parameters like audio volume, light intensity, and motor speed. You encounter potentiometers daily in devices such as stereo volume knobs, light dimmer switches, and speed controllers for fans, where they translate a simple physical adjustment into a smooth electrical change.

How Does a Potentiometer Work?

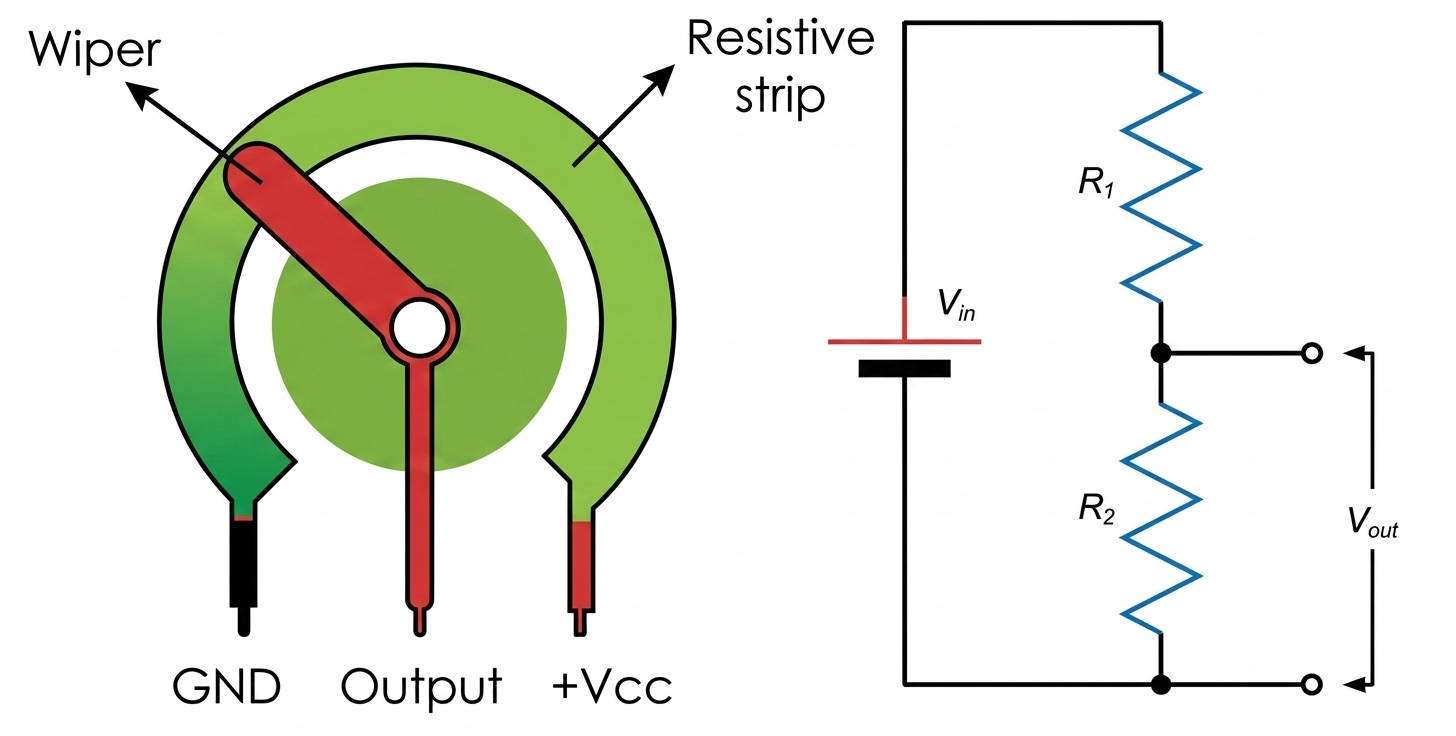

The internal operation of a potentiometer is based on the voltage divider principle. Imagine you have a uniform strip of resistive material; applying a voltage across its entire length creates a voltage gradient from one end to the other. A potentiometer introduces a sliding contact, called a wiper, that taps into this gradient at any point. The voltage measured between the wiper and one end is therefore a fraction of the total input voltage, determined by the wiper’s position.

- Resistive Element:This is the core track, made from materials like carbon, conductive plastic, or wire, which provides a set total resistance (e.g., 10kΩ).

- Wiper (Sliding Contact):This movable arm makes electrical contact with the resistive track. Its position is controlled by the user via a shaft or slider.

- Terminals:A standard potentiometer has three terminals. The two outer terminals connect to each end of the resistive element, and the center terminal connects to the wiper.

Main Parts of a Potentiometer

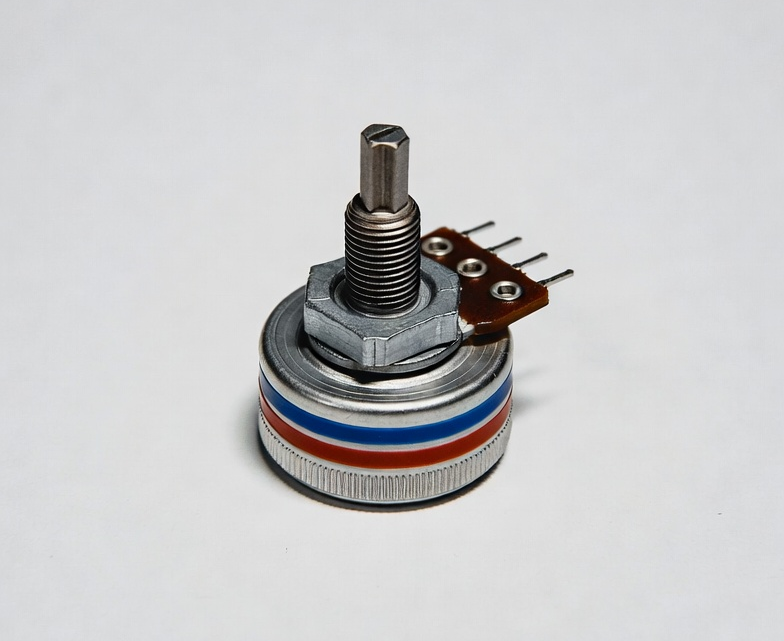

While designs vary, most rotary or slide potentiometers consist of a common set of physical components that house and facilitate the electrical working principle.

- Resistive Track:The path of resistive material that establishes the total resistance value and the voltage gradient.

- Wiper:The sliding contact that moves across the track, picking off the desired voltage.

- Terminals:The three (or sometimes more) connection points soldered to a circuit board or wired into a system.

- Shaft or Slider:The user interface. In a rotary pot, turning the shaft moves the wiper along a circular track. In a linear pot, pushing a slider moves it along a straight track.

- Housing:The casing that protects the internal components from dust and physical damage.

Types of Potentiometers

Potentiometers are categorized by their method of adjustment and their application, each suited to different tasks. The main categories are:

- Rotary Potentiometer:The most common type, adjusted by rotating a knob. These are ubiquitous as volume controls. They can be single-turn or multi-turn, with the latter offering very fine adjustment for precision calibration.

- Linear (Slider) Potentiometer:Adjusted by sliding a control in a straight line. Often called “faders,” these are standard on audio mixing boards and graphic equalizers, as a row of them provides a clear visual representation of settings.

- Digital Potentiometer (“Digipot”):An integrated circuit that mimics the function of a mechanical pot but is controlled by digital signals. Digipots are not adjusted by hand; instead, a microcontroller sends commands to change the wiper position. They are immune to mechanical wear, vibration, and contamination.

- Trimmer Potentiometer (“Trimpot”):A small, board-mounted potentiometer designed for occasional adjustment, typically with a screwdriver. Trimpots are used to calibrate or “trim” a circuit during manufacturing or repair and are not intended for frequent user control.

Applications of Potentiometers

The ability to provide a variable voltage or resistance makes potentiometers invaluable across countless devices.

- Volume Control in Audio Systems:This is the classic application. A potentiometer adjusts the signal level to an amplifier. Logarithmic taper pots are specifically used here to match the human ear’s non-linear perception of loudness.

- Light Dimmers:In dimmer switches, a potentiometer regulates a control signal that dictates how much power is delivered to the light, varying its brightness.

- Speed Control in Motors:By varying the voltage supplied to a DC motor, a potentiometer can directly control its rotation speed, useful in fans, toys, and small tools.

- Position and Angle Sensing:In joysticks, throttle pedals, or sensor arms, the physical position of the control directly correlates to the wiper’s position, outputting a corresponding voltage that a microcontroller can read.

- Calibration in Electronic Circuits:Trimmer potentiometers are essential for setting reference voltages, tuning oscillator frequencies, or balancing circuits after they are built.

Potentiometer vs Variable Resistor

The terms “potentiometer” and “variable resistor” are often used interchangeably, but there is a key technical distinction rooted in their configuration and primary function.

| Feature | Potentiometer | Variable Resistor (Rheostat) |

| Function | Primarily used as a voltage divider to provide a variable output voltage. | Primarily used to control current in a circuit by varying resistance. |

| Terminals | Three-terminal device. All three terminals are typically used. | Configured as a two-terminal device. Often, a three-terminal pot is wired to use only two. |

| Usage | Common in user-facing controls for continuous adjustment (volume, brightness). | Often used for calibration or in high-power applications (like motor control) where they handle more current. |

Advantages and Limitations of Potentiometers

Like any component, potentiometers have specific strengths and weaknesses that guide their use.

- Advantages:They boast a simple, intuitive design that is easy to understand and implement. They are generally low-cost components and offer a wide resistance range. Their operation is straightforward, providing analog control that feels natural to users.

- Limitations:The primary drawback is mechanical wear. The sliding contact and resistive track can degrade over time, leading to noise, unreliable contact, or failure. They are also sensitive to environmental factors like dust and humidity, can generate electrical noise, and generally have limited precision and bandwidth compared to fully digital solutions.

Conclusion

In summary, a potentiometer is a versatile and indispensable variable resistor that enables precise control in electronic circuits through the simple yet powerful voltage divider principle. From the volume knob on your speaker to the calibration controls inside sophisticated industrial machinery, its role in translating physical movement into an electrical signal is foundational. Understanding how potentiometers work opens the door to exploring a wider family of related components, such as fixed resistors for limiting current and rheostats for high-power variable resistance applications. Their enduring presence in both analog and digital worlds is a testament to their fundamental utility in electrical engineering and circuit design.