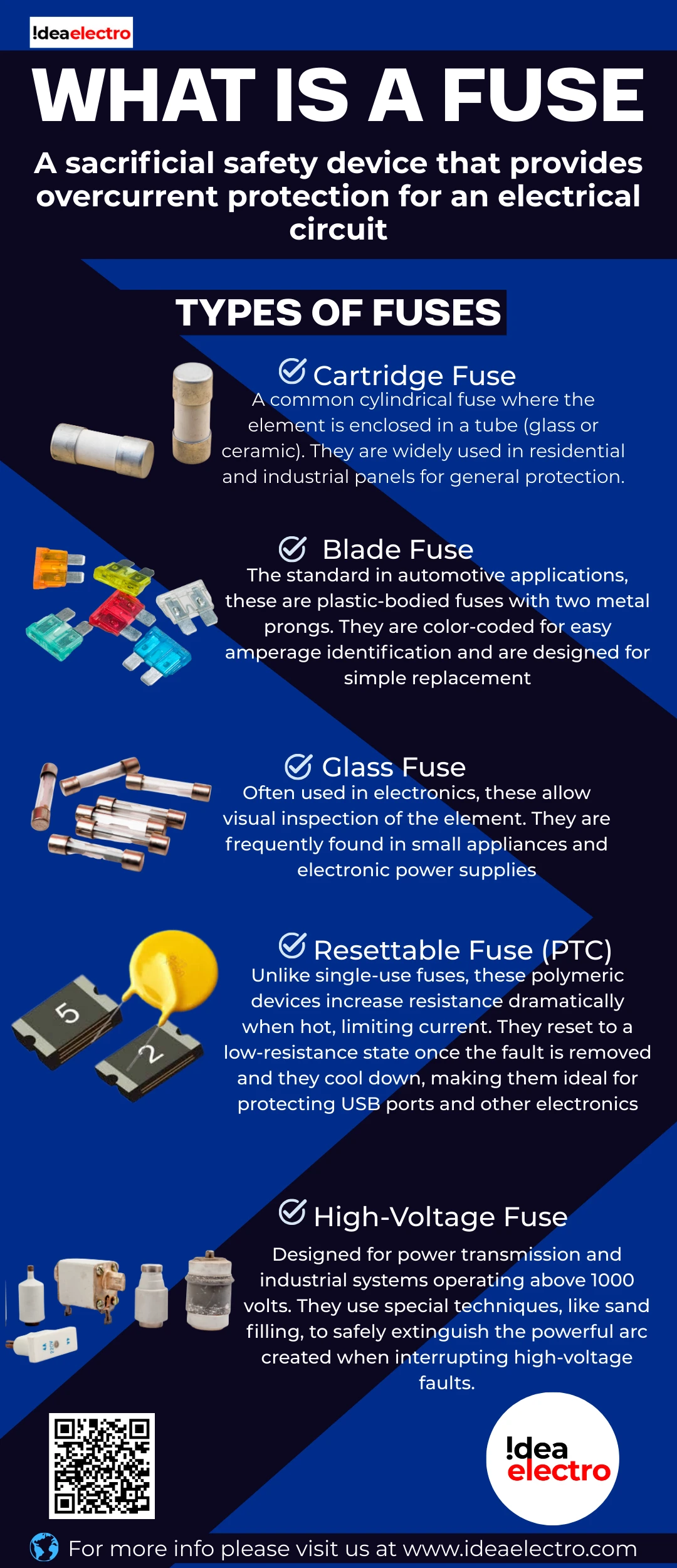

An electrical fuse is defined as a sacrificial safety device that provides overcurrent protection for an electrical circuit. Its primary purpose is to act as a deliberate “weak link” within the circuit. It contains a calibrated conductor that melts when the current flowing through it exceeds a predetermined safe level for a sufficient time. By melting and breaking the connection, the fuse interrupts the current flow entirely. This action prevents the excessive current—which generates dangerous heat—from reaching and damaging more expensive and critical components downstream, such as appliance motors, sensitive electronics, or building wiring.

How Does a Fuse Work?

A fuse operates on a straightforward thermal principle, responding directly to the heat generated by electrical current. Under normal operating conditions, the current passing through the fuse’s internal element generates a manageable amount of heat, which dissipates without harming the element. However, an overcurrent situation, which can be either an overload (2-5 times normal current) or a severe short circuit (tens to thousands of times normal current), drastically changes this balance. The excessive current rapidly generates more heat within the fuse element than it can dissipate.

- Excess Current Situation: This abnormal current flow can be caused by a short circuit, a failed component, or connecting too many devices to a single circuit.

- Fuse Element Melting: The heat causes the temperature of the fuse element—a metal wire or strip made from materials like tin, copper, or silver—to rise until it reaches its melting point.

- Circuit Break for Safety: Once the element melts, it physically severs, creating an open gap in the circuit. This interrupts all current flow, stopping the fault and isolating the protected circuit.

Main Components of a Fuse

Although designs vary, most fuses share three essential components that work together to provide reliable protection. The fuse element is the core functional part, a precisely engineered metal conductor designed to melt at a specific current. It is housed within a fuse body or casing, typically made from ceramic, glass, or plastic, which insulates the element and contains any arc or debris when it blows. Finally, metal end caps or terminals connect the fuse to the external circuit, ensuring all current flows through the protective element inside.

Types of Fuses

To meet diverse application needs, fuses are manufactured in various forms, each with distinct characteristics.

- Cartridge Fuse: A common cylindrical fuse where the element is enclosed in a tube (glass or ceramic). They are widely used in residential and industrial panels for general protection.

- Blade Fuse: The standard in automotive applications, these are plastic-bodied fuses with two metal prongs. They are color-coded for easy amperage identification and are designed for simple replacement.

- Glass Fuse: Often used in electronics, these allow visual inspection of the element. They are frequently found in small appliances and electronic power supplies.

- Resettable Fuse (PTC): Unlike single-use fuses, these polymeric devices increase resistance dramatically when hot, limiting current. They reset to a low-resistance state once the fault is removed and they cool down, making them ideal for protecting USB ports and other electronics.

- High-Voltage Fuse: Designed for power transmission and industrial systems operating above 1000 volts. They use special techniques, like sand filling, to safely extinguish the powerful arc created when interrupting high-voltage faults.

Fuse Rating and Specifications

Selecting the correct fuse is critical and is governed by specific ratings. The current rating, measured in amperes (A), indicates the maximum current the fuse can carry continuously without blowing. Equally important is the voltage rating, which must be equal to or greater than the circuit’s voltage to ensure the fuse can safely extinguish the arc when it opens. Using a fuse with an incorrect rating, such as one with too high a current rating, eliminates its protective function and creates a serious safety hazard.

Uses of Fuses in Daily Life

Fuses are ubiquitous safety components. In household wiring, they protect individual branch circuits for lighting and outlets, though they are often superseded by circuit breakers in modern panels. Countless electronic devices, from televisions to laptop chargers, contain internal fuses to safeguard their delicate circuitry. Modern automobiles rely on fuse boxes full of blade fuses to protect everything from headlights and radios to engine control units. Finally, industrial equipment uses high-capacity fuses to protect heavy machinery, motors, and power distribution systems where reliability is paramount.

Fuse vs Circuit Breaker

Both fuses and circuit breakers are overcurrent protective devices, but they differ significantly in operation and application. The table below summarizes key distinctions.

| Feature | Fuse | Circuit Breaker |

| Reset Capability | One-time use; must be replaced after operating. | Reusable; can be reset after tripping. |

| Cost | Generally lower initial cost. | Higher initial cost but can be more economical long-term. |

| Response Speed | Typically very fast, offering precise current limitation. | Can be slightly slower, though designed to meet safety standards. |

| Reusability | Sacrificial; not reusable. | Designed for many operations over its lifespan. |

Advantages and Limitations of a Fuse

The design of a fuse offers several distinct benefits. Its simple design with no moving parts translates to high reliability and zero maintenance. It is typically a low-cost solution for providing overcurrent protection. Furthermore, fuses generally have a very fast response time to severe short circuits, effectively limiting the energy that reaches downstream components. However, these advantages come with inherent limitations. Their primary drawback is that they are for one-time use only and must be replaced after blowing. This need for replacement can lead to downtime and requires users to have spares available.

Conclusion

In summary, a fuse is a vital, intentionally weak link in an electrical circuit that sacrifices itself to prevent damage from overcurrent. Its simple yet effective principle of operation has made it a cornerstone of electrical safety for over a century. Whether in a home, vehicle, or industrial machine, using a fuse with the proper current and voltage rating is non-negotiable for effective protection. As a final reminder, always investigate and correct the cause of a blown fuse before replacing it, and never substitute a fuse with one of a higher rating, as this compromises safety and invites risk.