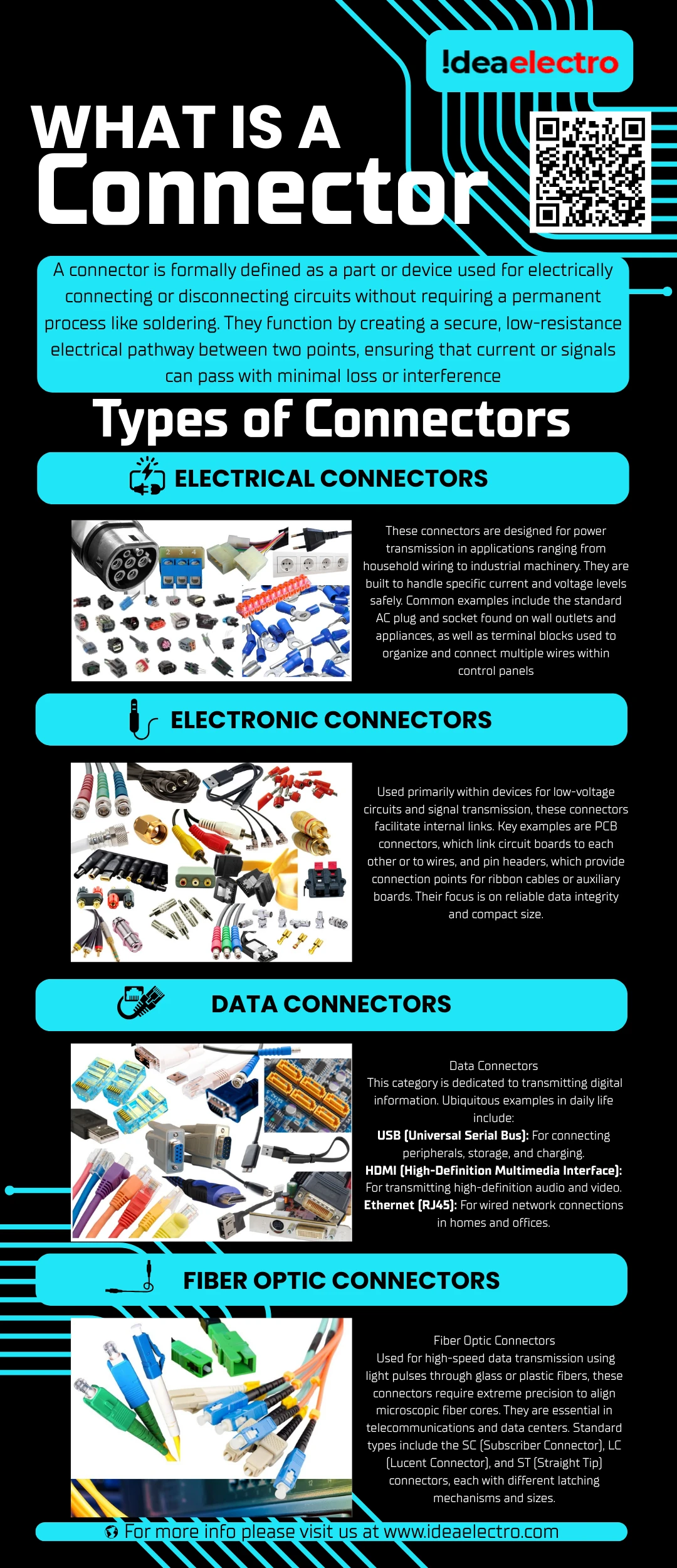

A connector is formally defined as a part or device used for electrically connecting or disconnecting circuits without requiring a permanent process like soldering. They function by creating a secure, low-resistance electrical pathway between two points, ensuring that current or signals can pass with minimal loss or interference. This is distinct from permanent connections, such as soldered joints or wire splices, which are fixed and not designed for regular separation. The core working principle of a connector involves physical contacts—usually metal pins and sockets—that mate together. When connected, these contacts touch, closing the circuit. The connector’s housing, typically made from insulating material, holds the contacts in precise alignment and prevents accidental short circuits. The simplicity and effectiveness of this principle underpin a vast array of technologies, from the smallest electronic gadgets to massive industrial machinery.

Connector, the Essential Link in Modern Technology

An electrical connector is a fundamental component designed to join electrical circuits, allowing for the transmission of power and signals between different devices or sections of a system. In electrical and electronic systems, connectors are indispensable; they serve as the critical interfaces that enable functionality, modularity, and serviceability. Without these components, assembling complex devices, performing maintenance, or upgrading systems would be impractical. You interact with connectors daily, often without a second thought—when you charge your smartphone, plug headphones into a computer, or connect a laptop to a monitor. They are the unseen facilitators that power our phones, computers, and household appliances, making modern, interconnected technology possible.

Why Connectors Are Important

The significance of connectors extends far beyond simple linkage. Their design delivers key practical benefits:

- Easy Assembly and Disassembly: Connectors simplify manufacturing and installation by allowing components to be joined quickly, often by hand or with simple tools.

- Improved Safety and Reliability: Properly specified connectors provide safe, insulated connections. Their secure locking mechanisms prevent accidental disconnections that could cause failures.

- Facilitated Repair and Replacement: They enable a modular approach to maintenance. If a component fails, it can be disconnected and swapped out without replacing the entire system, saving time and cost.

- Support for Modular System Design: Connectors allow engineers to build systems from interchangeable, pre-assembled modules, enhancing design flexibility and enabling easier upgrades.

Main Parts of a Connector

While designs vary, most connectors share a few fundamental components that ensure a stable and secure connection:

- Contacts: These are the conductive elements, often gold- or tin-plated, that physically touch to establish the electrical path. They are responsible for conducting electricity from one side of the connector to the other.

- Housing: This is the insulating body, usually made from plastic or other composite materials. It serves multiple purposes: it provides insulationbetween contacts to prevent short circuits, protects the contacts from physical damage, and ensures proper alignment during mating.

- Terminals: These are the specific ends of the contacts where wires or printed circuit board (PCB) traces are attached, forming the connection to the broader circuit.

- Locking Mechanism: A crucial feature for reliability, this mechanism—which can be a latch, screw thread, or push-pull system—ensures a secure physical connection, preventing contacts from loosening due to vibration or movement.

Types of Connectors

The world of connectors is diverse, with specialized types developed for distinct functions. They can be broadly categorized by their primary application.

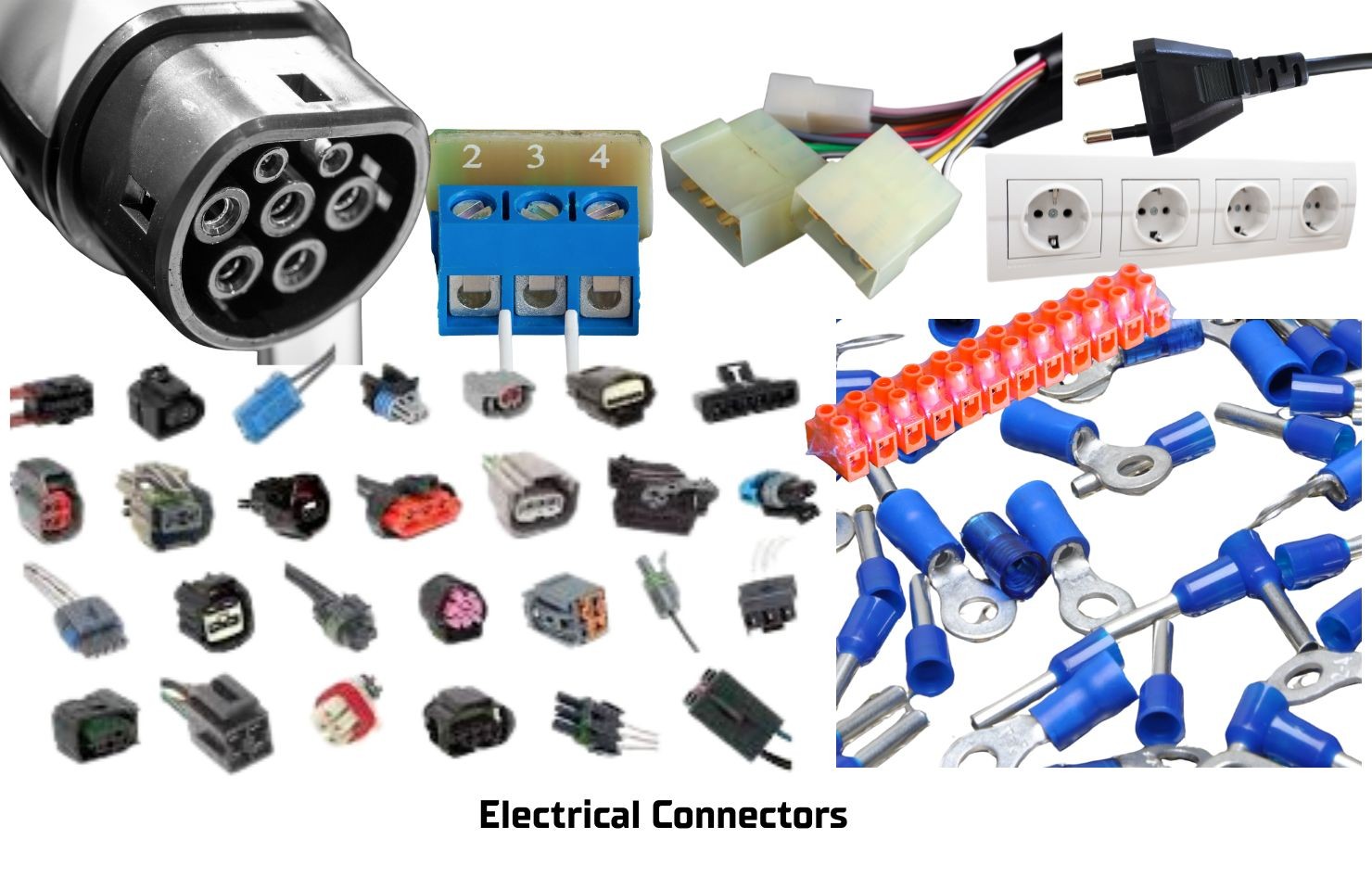

Electrical Connectors

These connectors are designed for power transmission in applications ranging from household wiring to industrial machinery. They are built to handle specific current and voltage levels safely. Common examples include the standard AC plug and socket found on wall outlets and appliances, as well as terminal blocks used to organize and connect multiple wires within control panels.

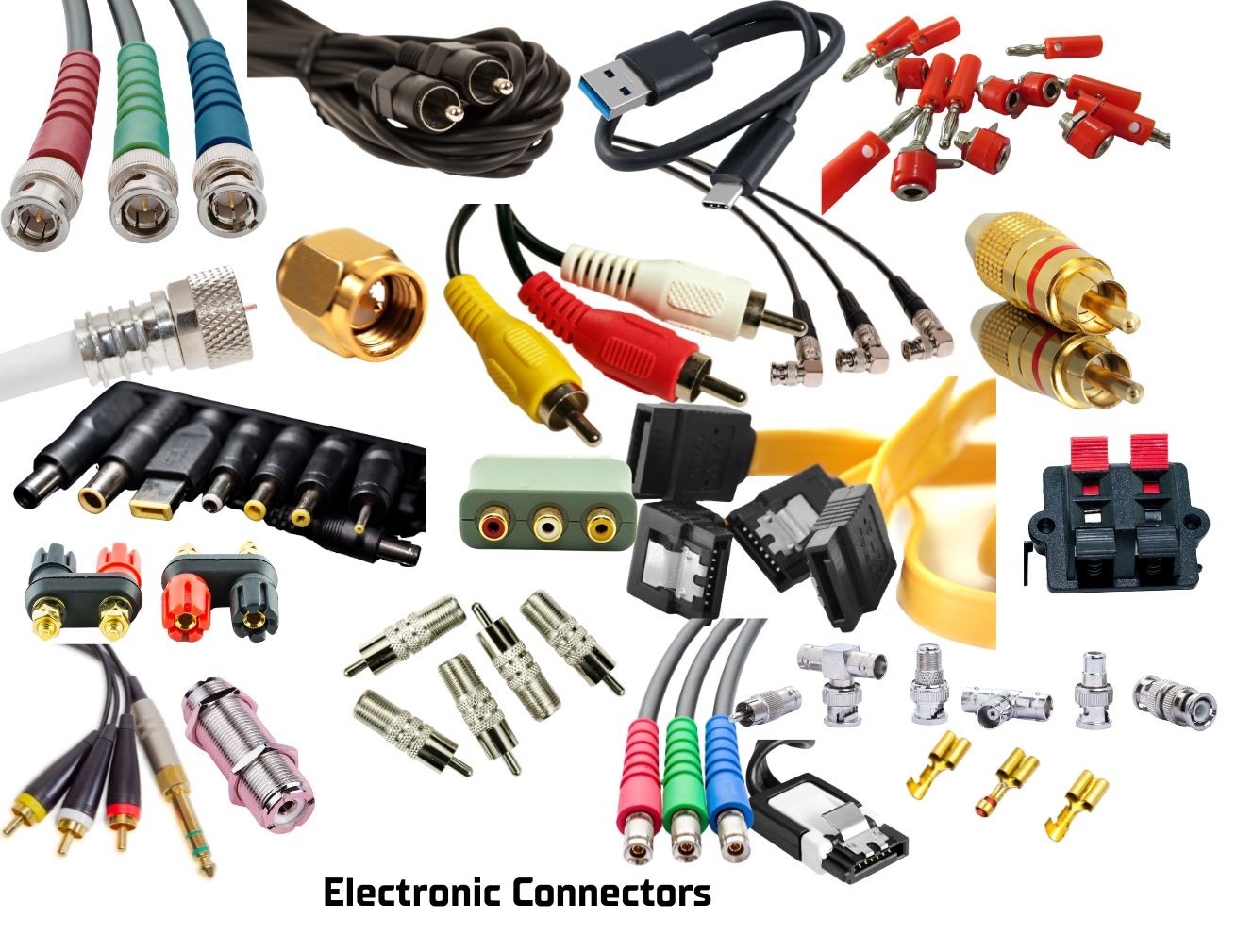

Electronic Connectors

Used primarily within devices for low-voltage circuits and signal transmission, these connectors facilitate internal links. Key examples are PCB connectors, which link circuit boards to each other or to wires, and pin headers, which provide connection points for ribbon cables or auxiliary boards. Their focus is on reliable data integrity and compact size.

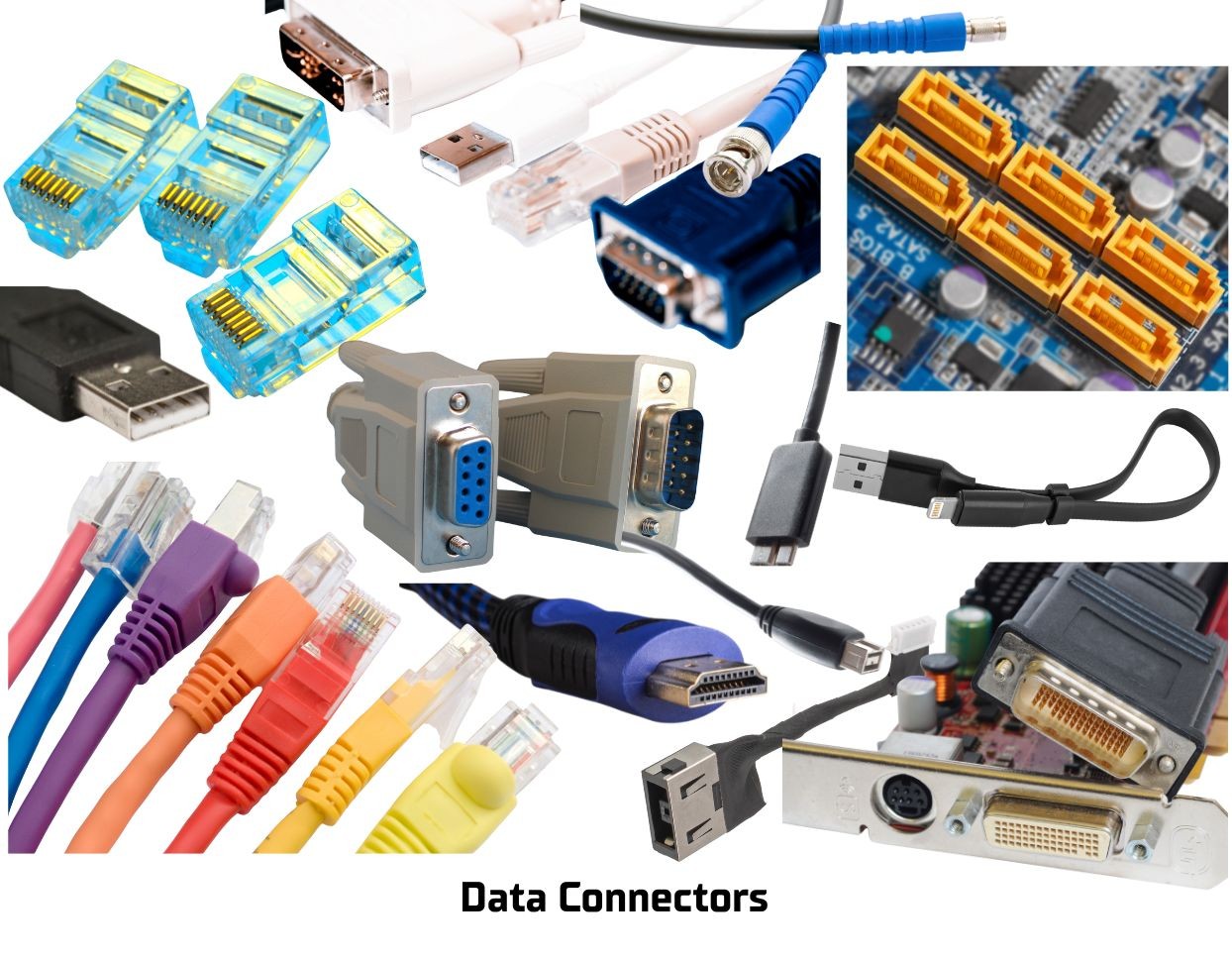

Data Connectors

This category is dedicated to transmitting digital information. Ubiquitous examples in daily life include:

- USB (Universal Serial Bus): For connecting peripherals, storage, and charging.

- HDMI (High-Definition Multimedia Interface): For transmitting high-definition audio and video.

- Ethernet (RJ45): For wired network connections in homes and offices.

Fiber Optic Connectors

Used for high-speed data transmission using light pulses through glass or plastic fibers, these connectors require extreme precision to align microscopic fiber cores. They are essential in telecommunications and data centers. Standard types include the SC (Subscriber Connector), LC (Lucent Connector), and ST (Straight Tip) connectors, each with different latching mechanisms and sizes.

Table: Common Connector Types and Their Primary Applications

| Connector Type | Primary Function | Common Examples | Typical Applications |

| Electrical | Power Transmission | Plug/Socket, Terminal Block | Appliance wiring, Industrial power |

| Electronic | Board & Signal Linkage | PCB Connector, Pin Header | Consumer electronics, Computer motherboards |

| Data | Digital Signal Transmission | USB, HDMI, Ethernet (RJ45) | Computer peripherals, Networking, Home theater |

| Fiber Optic | High-Speed Optical Data | SC, LC, ST Connectors | Telecom networks, Data centers, Internet backbone |

| Circular (Industrial) | Rugged Power & Signal | M8, M12, M23 Series | Factory automation, Robotics, Process control |

How Connectors Are Classified

Beyond their application, connectors can be systematically classified according to several key attributes, which helps in selecting the right component for a job:

- By Function: This is the primary classification, distinguishing connectors meant for power, signal, or data

- By Connection Method: This refers to how the connector mates. Common methods include plug-in(e.g., USB), screw-type (e.g., terminal blocks), bayonet (a push-and-twist action), and soldered (for permanent PCB mounting).

- By Environment: Connectors are rated for specific operating conditions, such as indoor(office/benign), outdoor (weather-resistant), or harsh industrial environments (resistant to dust, water, vibration, and extreme temperatures).

Advantages and Limitations of Connectors

Like any component, connectors present a balance of strengths and weaknesses that must be considered in design.

Advantages:

- Easy Installation: They enable quick assembly and wiring without specialized soldering in many cases.

- Reusable: Designed for multiple mating cycles, they allow for reconfiguration and repair.

- Cost-Effective: By simplifying production and maintenance, they reduce overall system costs.

Limitations:

- Wear and Tear: Contacts and housings can degrade over time with repeated connection and disconnection, potentially leading to increased resistance or failure.

- Signal Loss: Poor-quality connectors or those not matched to the signal type can introduce resistance, capacitance, or interference, degrading signal integrity.

Applications of Connectors

The utility of connectors spans virtually every sector of technology:

- Consumer Electronics: Enabling compact, modular design in smartphones, laptops, and gaming systems.

- Automotive Systems: Used throughout modern vehicles for infotainment, sensors, engine control units, and lighting.

- Industrial Machinery: Rugged connectors ensure reliable operation of robots, conveyor systems, and programmable logic controllers (PLCs) in harsh factory conditions.

- Medical Equipment: Providing reliable, sometimes sterilizable, connections in diagnostic and life-support devices where failure is not an option.

- Communication Systems: Forming the physical backbone of data networks, from fiber optic internet cables to cellular base stations.

How to Choose the Right Connector

Selecting the appropriate connector is critical for system performance and safety. Key factors to evaluate include:

- Electrical Requirements: Verify the connector’s voltage and current ratingto ensure it can handle the circuit’s power needs without overheating or breaking down.

- Compatibility: Ensure the connector type (form factor, pin layout, gender) matches the mating component. Codingfeatures on some connectors prevent mismating.

- Environmental Conditions: For demanding settings, check the Ingress Protection (IP) ratingfor dust/water resistance and the operational temperature range.

- Durability Requirements: Consider the expected number of mating cycles, and the need for resistance to shock, vibration, or chemicals based on the application.

Conclusion

In summary, connectors are far more than simple linking components; they are the fundamental enablers of modularity, serviceability, and innovation in electrical and electronic systems. Their role in ensuring reliable connections—for power, data, and signals—is irreplaceable across consumer, industrial, and medical technologies. As systems continue to advance in complexity and capability, the importance of selecting a connector that is precisely matched to its electrical, mechanical, and environmental demands only grows. Understanding the basic principles, types, and selection criteria for connectors is therefore essential for anyone involved in designing, maintaining, or simply appreciating the technological world around us.