In simple terms, a battery is a device that stores chemical energy and converts it into electrical energy. This distinguishes it from a direct power supply, like a wall outlet, which provides a continuous flow of electricity from the grid. A battery contains all the necessary components to generate electricity internally through controlled chemical reactions. When you connect a battery to a circuit—for example, by putting one into a flashlight—these reactions are initiated, causing a flow of electrons through your device and providing power. This capability to store potential energy for later use is the core of a battery’s function. From the moment we wake up and check a smartphone to using a remote control or a flashlight in the evening, batteries provide the essential, cord-free power that modern convenience relies on. Their importance extends beyond consumer gadgets to critical applications in medical equipment, transportation, and renewable energy systems. Fundamentally, a battery acts as a compact chemical energy reserve, ready to be converted into electrical energy on demand to perform work.

Main Components of a Battery

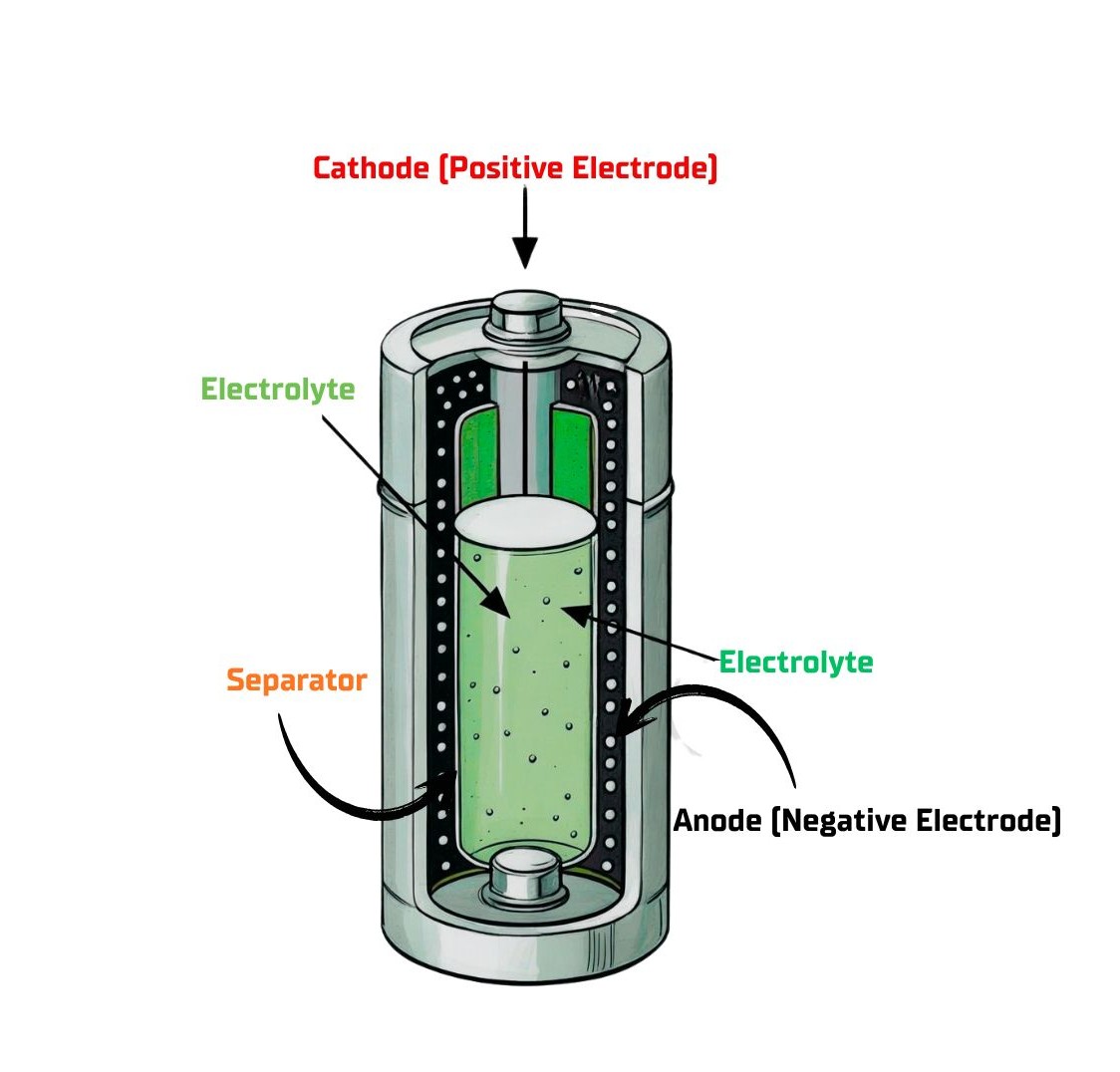

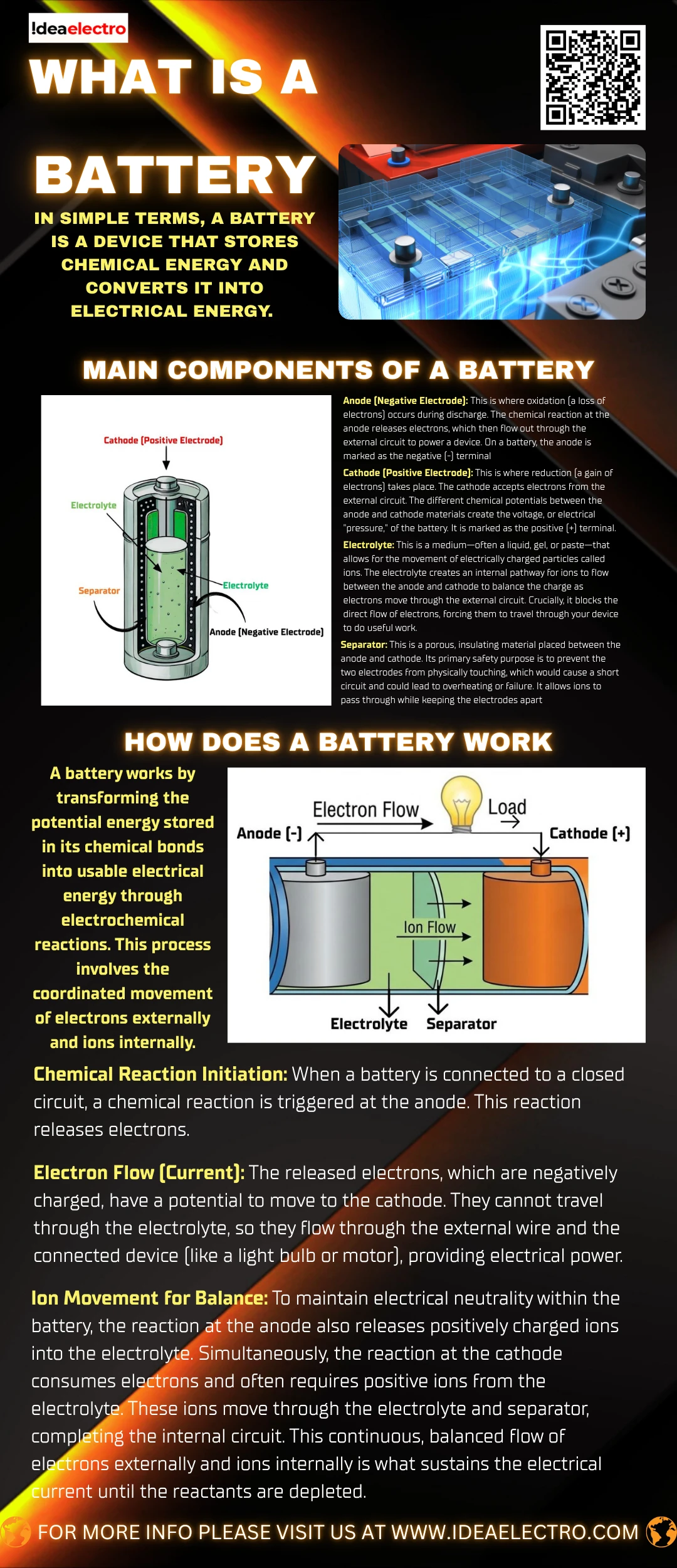

Every battery, regardless of its size or type, is built from a few essential parts that work together:

- Anode (Negative Electrode):This is where oxidation (a loss of electrons) occurs during discharge. The chemical reaction at the anode releases electrons, which then flow out through the external circuit to power a device. On a battery, the anode is marked as the negative (-) terminal.

- Cathode (Positive Electrode):This is where reduction (a gain of electrons) takes place. The cathode accepts electrons from the external circuit. The different chemical potentials between the anode and cathode materials create the voltage, or electrical “pressure,” of the battery. It is marked as the positive (+) terminal.

- Electrolyte:This is a medium—often a liquid, gel, or paste—that allows for the movement of electrically charged particles called ions. The electrolyte creates an internal pathway for ions to flow between the anode and cathode to balance the charge as electrons move through the external circuit. Crucially, it blocks the direct flow of electrons, forcing them to travel through your device to do useful work.

- Separator:This is a porous, insulating material placed between the anode and cathode. Its primary safety purpose is to prevent the two electrodes from physically touching, which would cause a short circuit and could lead to overheating or failure. It allows ions to pass through while keeping the electrodes apart.

How Does a Battery Work?

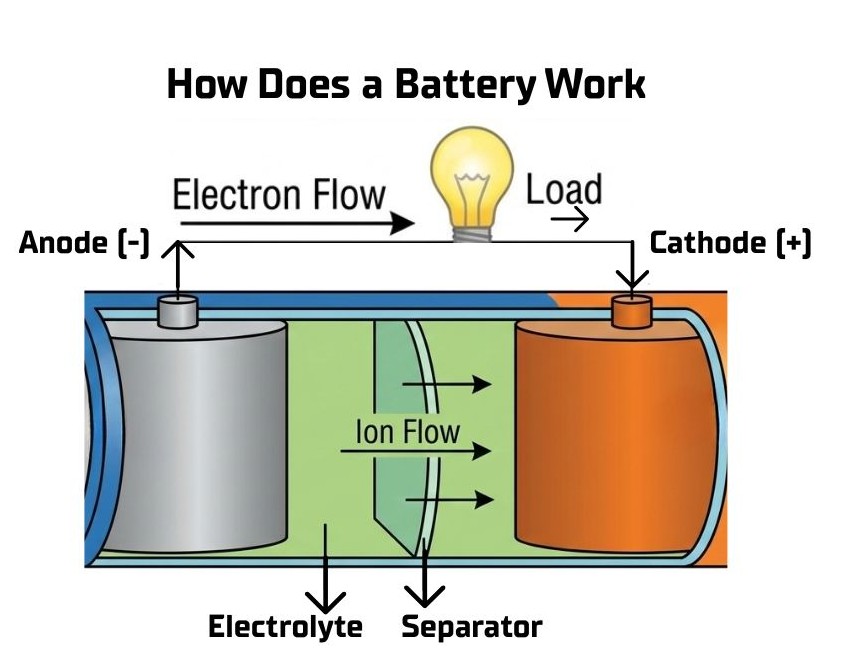

A battery works by transforming the potential energy stored in its chemical bonds into usable electrical energy through electrochemical reactions. This process involves the coordinated movement of electrons externally and ions internally.

Chemical Reaction Initiation: When a battery is connected to a closed circuit, a chemical reaction is triggered at the anode. This reaction releases electrons.

Electron Flow (Current): The released electrons, which are negatively charged, have a potential to move to the cathode. They cannot travel through the electrolyte, so they flow through the external wire and the connected device (like a light bulb or motor), providing electrical power.

Ion Movement for Balance: To maintain electrical neutrality within the battery, the reaction at the anode also releases positively charged ions into the electrolyte. Simultaneously, the reaction at the cathode consumes electrons and often requires positive ions from the electrolyte. These ions move through the electrolyte and separator, completing the internal circuit. This continuous, balanced flow of electrons externally and ions internally is what sustains the electrical current until the reactants are depleted.

Types of Batteries

Batteries are broadly classified into two categories based on whether their chemical reactions are reversible.

Primary Batteries (Non-Rechargeable)

Primary batteries are designed for single use. Once the chemical reactants are exhausted, the battery can no longer produce electricity and must be replaced. They are known for long shelf life and are typically used in devices with low to moderate power demands or where recharging is impractical.

- Common Examples:Standard consumer sizes like AA, AAA, C, and D cells, which are often alkaline Lithium metal batteries (non-rechargeable) are another type, offering higher energy density and longer life for devices like cameras and watches.

Secondary Batteries (Rechargeable)

Secondary batteries are based on reversible electrochemical reactions. When their stored energy is depleted, an external electrical current can be applied to reverse the reactions, restoring the battery’s chemical potential for another cycle of use. This makes them cost-effective and essential for high-drain electronics.

- Common Examples:

- Lithium-ion (Li-ion):The dominant technology in portable electronics and electric vehicles due to its high energy density, light weight, and relatively low self-discharge rate.

- Lead-Acid:A mature, reliable, and low-cost technology commonly used for automotive starting batteries and backup power systems, though it is heavy and has a lower energy density.

- Nickel-Metal Hydride (NiMH):Often found in hybrid electric vehicles, power tools, and older rechargeable consumer cells. They offer a good balance of capacity and cost but have a higher self-discharge rate than Li-ion.

Common Battery Sizes and Formats

Batteries come in standardized sizes and custom formats to fit diverse applications. The most familiar are cylindrical cells like AA (14.5mm x 50.5mm) and AAA (10.5mm x 44.5mm), which are ubiquitous in household electronics. Coin cells (or button cells), such as the CR2032, are small, disc-shaped batteries used to power watches, calculators, and computer motherboards. For higher voltage and capacity needs, multiple cells are assembled into rechargeable battery packs, like those in laptops, power tools, and electric vehicles. Finally, manufacturers often design custom battery shapes, including slim pouches, to maximize space in compact devices like smartphones and tablets.

Applications of Batteries

The portability and stored energy capacity of batteries enable a vast range of applications:

- Consumer Electronics:Powering the cordless operation of mobile phones, laptops, tablets, and wearable devices.

- Transportation:Providing the primary energy source for electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrids, and serving crucial functions in starting, lighting, and ignition for conventional cars.

- Medical Devices:Ensuring the reliable, often life-sustaining, operation of portable equipment like insulin pumps, heart rate monitors, and hearing aids.

- Renewable Energy Storage:Storing energy generated by solar panels and wind turbines for use when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing, which is critical for grid stability and off-grid power systems.

Advantages and Limitations of Batteries

Advantages:

Batteries provide the paramount benefit of portable power, enabling the design and use of mobile, cordless devices that would otherwise be tethered to an outlet. They are also generally easy to use, requiring minimal setup for basic applications.

Limitations:

All batteries have a limited lifespan, dictated by the number of charge-discharge cycles (for rechargeable) or total energy capacity (for disposables). Charging time can be a constraint, especially for large-capacity batteries like those in EVs. Furthermore, there is a significant environmental impact associated with the extraction of raw materials (e.g., lithium, cobalt, lead) and the challenges of recycling complex battery components at their end of life.

Battery Safety and Proper Usage

Safe handling extends battery life and prevents hazards. Key guidelines include:

- Avoid overchargingrechargeable batteries, as it can lead to overheating and reduce longevity.

- Do not expose batteries to extreme heat(like leaving them in a hot car) or attempt to disassemble them, as this can cause leakage, rupture, or fire.

- Practice proper disposal and recycling.Never dispose of batteries in regular trash. Use designated recycling programs to recover valuable materials and prevent toxic substances from contaminating the environment.

Conclusion

In summary, a battery is an electrochemical device that stores chemical energy and converts it into electrical energy on demand through controlled internal reactions. Its core components—the anode, cathode, electrolyte, and separator—work in concert to generate a flow of electrons that can power everything from tiny earpieces to electric cars. As the enabling technology for portable electronics, clean transportation, and renewable energy integration, batteries are a cornerstone of modern electrical engineering. Ongoing research continues to focus on improving their capacity, safety, sustainability, and cost, ensuring they will remain vital to technological progress.