A Printed Circuit Board (PCB) is a flat, usually rigid board constructed from a non-conductive substrate, like fiberglass, onto which conductive pathways are precisely patterned. These thin copper pathways, called traces, in essence, a PCB provides two core functions: mechanical support to hold components in place and electrical connections to allow signals and power to flow between them. Printed Circuit Boards (PCBs) are essential components found inside nearly all modern electronic devices. They serve as the foundation for mounting and connecting electronic parts such as resistors, chips, and microprocessors, Without PCBs, modern electronics as we know them—characterized by miniaturization, reliability, and complexity—would not be possible. A. PCBs replaced older point-to-point wiring systems. The printed manufacturing process allows precise, compact, and repeatable circuit designs that make modern electronics possible.

Main Components of a Printed Circuit Board

A standard PCB is built like a layer cake, with each layer serving a distinct purpose in the board’s function and durability. The primary components include:

- Substrate (Base Material):This is the foundational layer, typically made of a fiberglass-reinforced epoxy known as FR-4. It provides the board with its rigid structure and electrically insulates the conductive layers.

- Copper Layers:Thin sheets of copper foil are laminated onto the substrate. This copper is then etched away to form the specific network of traces and connection pads that define the circuit.

- Solder Mask:The familiar green (or other colored) coating on a PCB is the solder mask. This protective layer is applied over the copper to insulate the traces and prevent accidental short circuits during soldering. It also shields the copper from environmental damage.

- Silkscreen:The white (or other colored) markings on top of the solder mask form the silkscreen layer. This legend includes labels, symbols, and component outlines to assist engineers in assembly, debugging, and repair by identifying parts and their orientations.

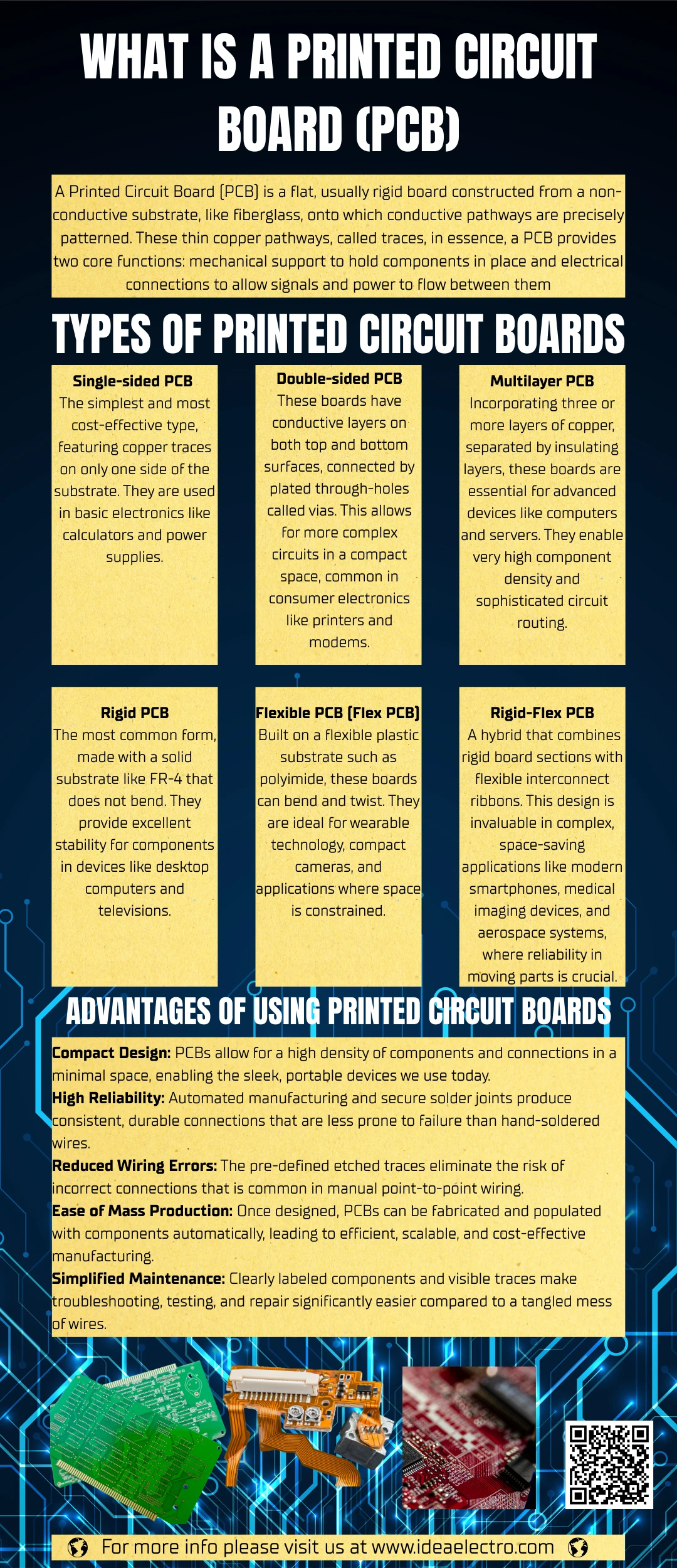

Types of Printed Circuit Boards

Different electronic applications demand different PCB characteristics, leading to a variety of board types. The most common classifications are based on the number of conductive layers and the board’s physical flexibility.

- Single-sided PCB:The simplest and most cost-effective type, featuring copper traces on only one side of the substrate. They are used in basic electronics like calculators and power supplies.

- Double-sided PCB:These boards have conductive layers on both top and bottom surfaces, connected by plated through-holes called vias. This allows for more complex circuits in a compact space, common in consumer electronics like printers and modems.

- Multilayer PCB:Incorporating three or more layers of copper, separated by insulating layers, these boards are essential for advanced devices like computers and servers. They enable very high component density and sophisticated circuit routing.

- Rigid PCB:The most common form, made with a solid substrate like FR-4 that does not bend. They provide excellent stability for components in devices like desktop computers and televisions.

- Flexible PCB (Flex PCB):Built on a flexible plastic substrate such as polyimide, these boards can bend and twist. They are ideal for wearable technology, compact cameras, and applications where space is constrained.

- Rigid-Flex PCB:A hybrid that combines rigid board sections with flexible interconnect ribbons. This design is invaluable in complex, space-saving applications like modern smartphones, medical imaging devices, and aerospace systems, where reliability in moving parts is crucial.

How a Printed Circuit Board Works

The fundamental operation of a PCB is to provide controlled pathways for electrical current and signals. When a device is powered on, electricity flows from the power source through the copper traces. These traces act as predetermined highways, routing power to components and facilitating signal communication between them. For example, in a simple LED circuit, current travels from a battery connector through a trace to a current-limiting resistor, then to the LED, causing it to light up, before completing the loop back to the power source. In complex devices like smartphones, millions of connections on multi-layer boards work simultaneously. The physical layout of these traces is not random; it is meticulously designed to manage signal integrity, prevent interference, ensure stable power distribution, and often to manage heat, which directly impacts the device’s performance and reliability.

Materials Used in Printed Circuit Boards

The choice of materials directly impacts a PCB’s performance, durability, and suitability for specific environments. Key materials include:

- FR-4:A flame-retardant, fiberglass-reinforced epoxy laminate. It is the industry-standard substrate for rigid PCBs due to its good mechanical strength, electrical insulation, and cost-effectiveness.

- Copper:The primary conductive material. Thin copper foil is laminated onto the substrate and etched to form the circuit pattern. Its thickness can be varied depending on the current-carrying requirements of the board.

- Aluminum:Often used as a metal core in specialized PCBs for high-power LED lighting and automotive systems. Its primary function is not conduction but rather to act as a highly effective heat sink, drawing excess thermal energy away from sensitive components.

- Polyimide:A high-temperature, flexible polymer that serves as the base material for flexible and rigid-flex PCBs. It offers exceptional heat resistance, chemical stability, and can withstand repeated bending, making it essential for advanced applications in aerospace, medical devices, and consumer electronics.

Applications of Printed Circuit Boards

The universality of PCBs is a testament to their versatility. They are integral to nearly every sector of technology.

- Consumer Electronics:PCBs are the heart of smartphones, laptops, televisions, and gaming consoles, where the drive for miniaturization and high performance is relentless.

- Medical Devices:From life-critical equipment like pacemakers, MRI machines, and infusion pumps to monitoring devices, medical PCBs must meet exceptionally high standards for reliability and precision.

- Automotive Systems:Modern vehicles contain dozens of PCBs controlling everything from engine management units and infotainment systems to advanced driver-assistance sensors (ADAS) and LED lighting.

- Industrial Machinery:In manufacturing and automation, robust PCBs control heavy machinery, robotics, and power supplies, often designed to withstand harsh conditions like vibration, dust, and extreme temperatures.

- Telecommunications:Network infrastructure, including routers, switches, and cellular base stations, relies on complex, high-speed PCBs to manage data transmission and connectivity.

Advantages of Using Printed Circuit Boards

The widespread adoption of PCBs over traditional wiring is driven by several compelling advantages:

- Compact Design:PCBs allow for a high density of components and connections in a minimal space, enabling the sleek, portable devices we use today.

- High Reliability:Automated manufacturing and secure solder joints produce consistent, durable connections that are less prone to failure than hand-soldered wires.

- Reduced Wiring Errors:The pre-defined etched traces eliminate the risk of incorrect connections that is common in manual point-to-point wiring.

- Ease of Mass Production:Once designed, PCBs can be fabricated and populated with components automatically, leading to efficient, scalable, and cost-effective manufacturing.

- Simplified Maintenance:Clearly labeled components and visible traces make troubleshooting, testing, and repair significantly easier compared to a tangled mess of wires.

Printed Circuit Board vs Traditional Wiring

The evolution from traditional wiring to PCBs represents a quantum leap in electronics manufacturing, as summarized in the table below:

| Feature | Printed Circuit Board | Traditional Wiring |

| Size | Extremely compact, enabling miniaturization. | Bulky and space-consuming due to wire volume. |

| Reliability | High, with consistent, automated connections. | Lower, prone to loose connections and short circuits over time. |

| Maintenance | Easier, with organized layouts and clear markings. | Difficult, requiring tracing of individual wires in a complex bundle. |

| Production | Fully automated, ideal for mass production. | Largely manual, slow, and difficult to scale. |

This comparison highlights how PCBs solve the fundamental limitations of earlier methods, providing a foundation for modern electronics.

Importance of PCBs in Modern Electronics

PCBs are more than just a component; they are the essential platform upon which the digital age is built. Their importance lies in their role as the great enabler of miniaturization and functional complexity. By allowing millions of transistors and components to be interconnected reliably on a board sometimes no larger than a thumbnail, PCBs have made powerful computing portable and accessible. They are fundamental to the ongoing advancement of technology, from the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence to next-generation medical implants and sustainable energy systems. As long as electronics continue to evolve, the printed circuit board will remain at its core, adapting to meet new challenges in speed, density, and application.

Conclusion

In summary, a Printed Circuit Board is a sophisticated yet fundamental structure that mechanically supports and electrically connects the components of an electronic device. Through its layered construction of substrate, copper, and protective coatings, and in various forms such as rigid, flexible, or multilayer, the PCB provides unmatched advantages in reliability, size, and manufacturing efficiency. Its applications span every technological field, making it indispensable to modern life. As electronic devices continue to evolve toward greater intelligence and connectivity, the innovation in PCB design and materials will undoubtedly continue to be a critical driver of this progress.