In technical terms, a sensor is a device, module, or subsystem designed to detect events or changes in its environment—known as stimuli—and send this information to other electronics, typically a computer processor. The core function involves measuring a physical quantity (the input), such as temperature, pressure, light, or motion, and converting it into a readable or usable electrical signal (the output). This process allows physical phenomena to be quantified, monitored, and acted upon by electronic circuits. Whether it’s a thermostat gauging room temperature or a camera capturing light, the sensor serves as the critical first point of contact, transforming real-world conditions into a language that machines can understand and process. Sensors play a vital role in modern life, from smartphone alarms and automatic car braking systems to homes that adjust temperature automatically. These devices act as a bridge between the physical world and digital technology by continuously detecting changes such as light, heat, motion, or pressure. A sensor is technically defined as a device or subsystem that detects environmental stimuli and converts physical quantities into usable electrical signals. This conversion allows electronic systems to measure, monitor, and respond to real-world conditions. Whether in thermostats, cameras, or smart devices, sensors enable automation, improve safety, and enhance efficiency across countless applications.

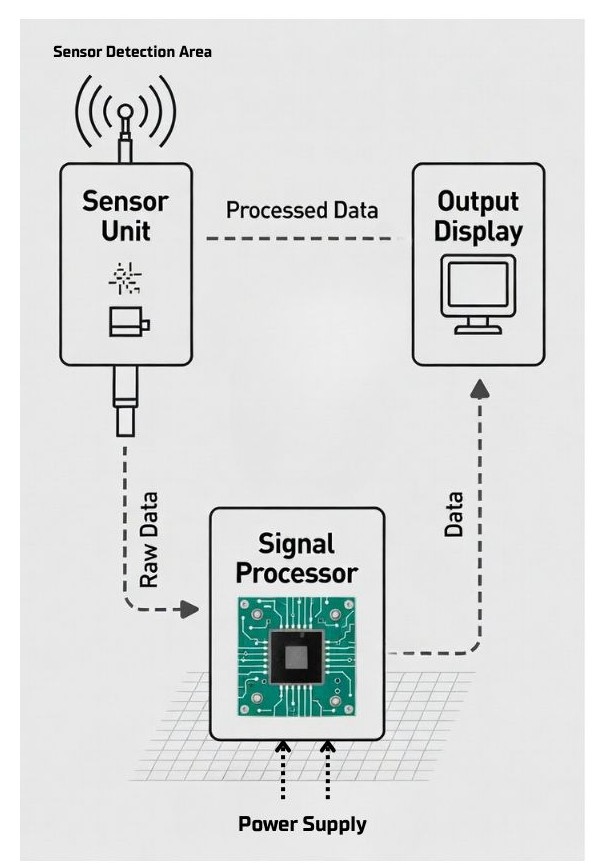

How Does a Sensor Work?

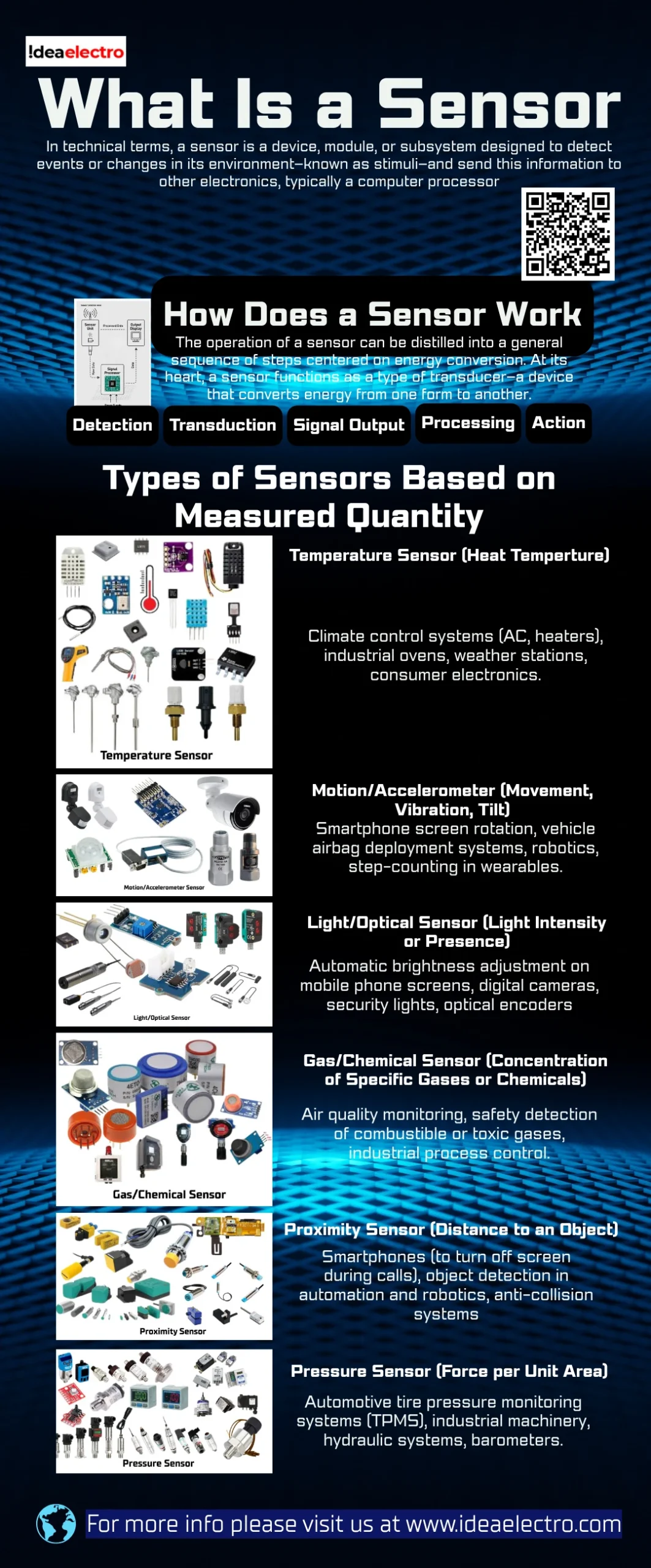

The operation of a sensor can be distilled into a general sequence of steps centered on energy conversion. At its heart, a sensor functions as a type of transducer—a device that converts energy from one form to another.

- Detection:The sensor’s sensing element is exposed to a physical property or condition in its environment (e.g., heat, force, or light).

- Transduction:This physical change causes a corresponding alteration in the properties of the sensing element. For example, a temperature change might modify a material’s electrical resistance.

- Signal Output:This internal change is converted into an electrical signal, such as a changing voltage, current, or resistance.

- Processing:The often-weak electrical signal is conditioned (amplified, filtered) and may be converted from analog to digital format for a computer or microcontroller to process.

- Action:The processed information is used to trigger a display, activate a control system, or store data for analysis, completing the chain from physical event to actionable data.

Main Components of a Sensor

While designs vary, many sensors incorporate a logical set of components to perform their task reliably. After detection, the typically weak or unsuited electrical signal from the transducer must be prepared for use by the broader system.

- Sensing Element:This is the core material or component that directly interacts with the measured physical quantity and changes its own properties as a result.

- Transducer:This component is responsible for converting the physical change in the sensing element into an electrical signal. In many simple sensors, the sensing element and transducer are the same component.

- Signal Conditioning Unit:This electronic circuit performs essential operations on the raw signal. It often includes amplifiers to boost the signal’s strength and filters to remove unwanted electrical “noise”.

- Output Interface:This is the final stage that delivers the processed signal in a standardized form (e.g., analog voltage, digital data stream, or a simple on/off state) that can be easily read by external devices like microcontrollers, displays, or control systems.

Types of Sensors Based on Measured Quantity

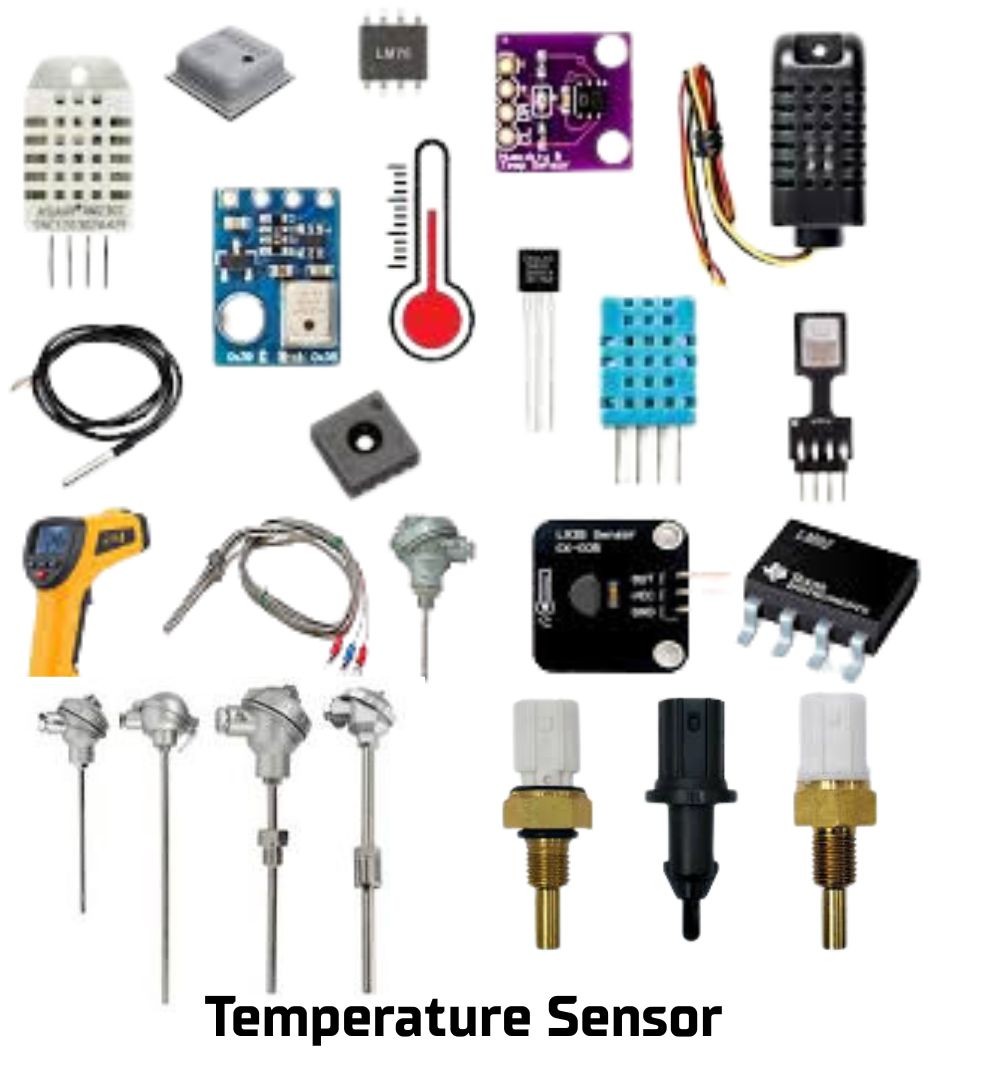

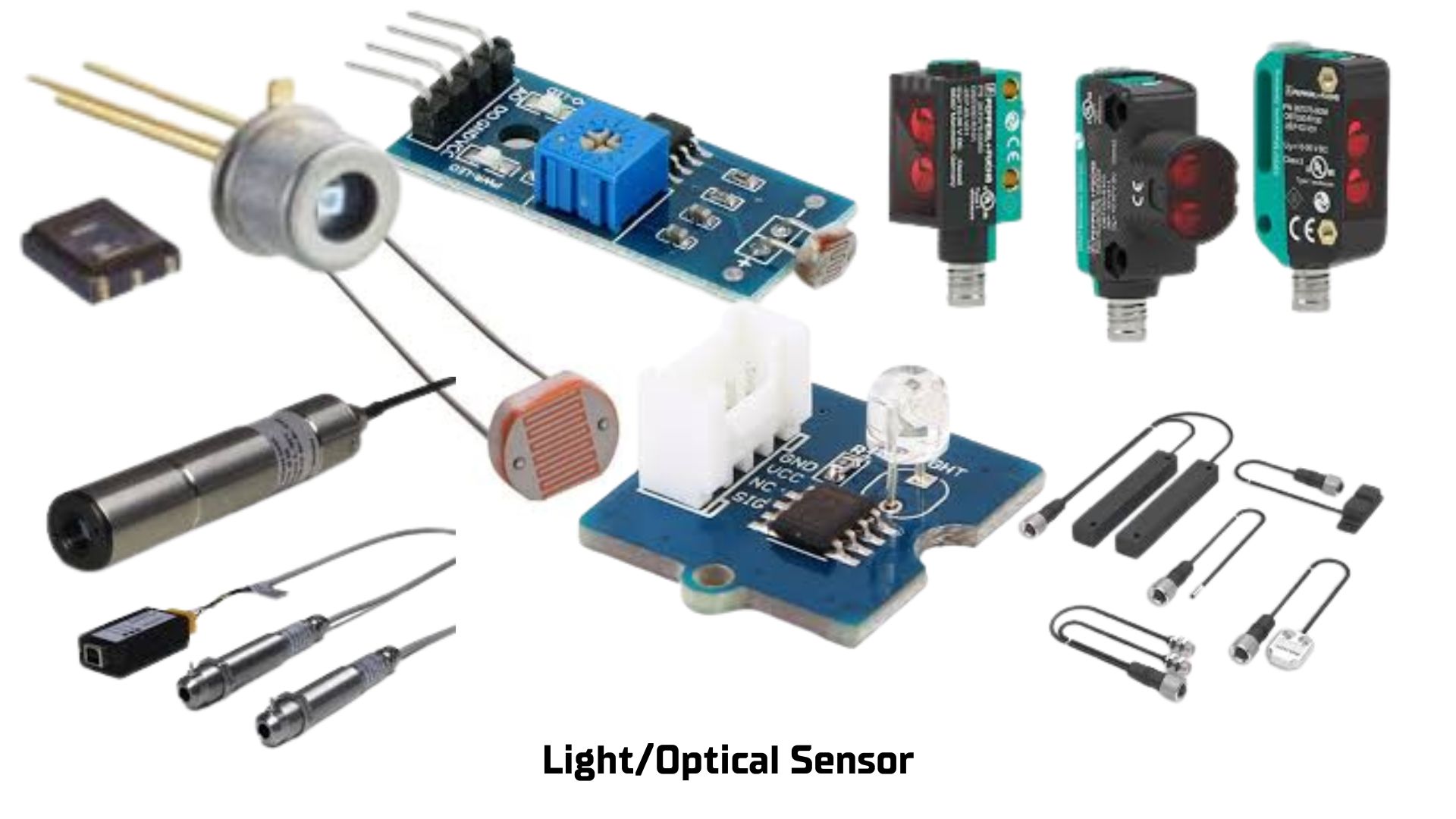

Sensors are most commonly categorized by the specific physical property they are designed to measure. This classification directly links the sensor’s purpose to its application across different fields. The table below outlines some of the most prevalent types.

| Sensor Type | Measures | Common Applications |

| Temperature Sensor | Heat (Temperature) | Climate control systems (AC, heaters), industrial ovens, weather stations, consumer electronics.

|

| Pressure Sensor | Force per Unit Area | Automotive tire pressure monitoring systems (TPMS), industrial machinery, hydraulic systems, barometers.

|

| Light/Optical Sensor | Light Intensity or Presence | Automatic brightness adjustment on mobile phone screens, digital cameras, security lights, optical encoders.

|

| Motion/Accelerometer | Movement, Vibration, Tilt | Smartphone screen rotation, vehicle airbag deployment systems, robotics, step-counting in wearables.

|

| Proximity Sensor | Distance to an Object | Smartphones (to turn off screen during calls), object detection in automation and robotics, anti-collision systems.

|

| Gas/Chemical Sensor | Concentration of Specific Gases or Chemicals | Air quality monitoring, safety detection of combustible or toxic gases, industrial process control.

|

Types of Sensors Based on Technology

Beyond what they measure, sensors can also be classified by their underlying operating technology and signal type. Analog sensors produce a continuous output signal (like a voltage) that is directly proportional to the measured quantity, requiring an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) for computer processing. In contrast, digital sensors provide discrete, binary (0 or 1) output signals or serial data, which are directly compatible with digital systems like microcontrollers.

Another key distinction is between active sensors, which require an external power source (excitation signal) to generate their output, and passive sensors, which generate their own output signal in response to the stimulus without needing external power. An emerging and powerful category is the smart sensor, which integrates a microprocessor, enabling onboard data processing, self-diagnosis, and direct communication within networked systems, greatly enhancing their functionality in automation.

Applications of Sensors in Daily Life

The practical importance of sensors is best illustrated by their integration into the fabric of daily life and industry. Their ability to provide real-time data is the foundation for smarter, more responsive systems.

- Consumer Electronics and Wearables:Smartphones use a suite of sensors (proximity, accelerometer, gyroscope, ambient light). Wearable fitness trackers monitor heart rate, movement, and sleep patterns.

- Automotive and Safety:Modern vehicles rely on networks of sensors for engine management, parking assistance, anti-lock braking systems (ABS), and advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) like automatic emergency braking.

- Healthcare:Medical equipment utilizes sensors for patient monitoring (heart rate, blood oxygen), diagnostic imaging, and sophisticated laboratory analysis, forming the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT).

- Smart Homes:Sensors enable home automation, with thermostats learning schedules, security systems detecting motion or windows being opened, and smoke detectors providing alerts.

- Industrial Automation:In manufacturing, sensors monitor machine health, control robotic arms, ensure quality control, and enable predictive maintenance, which is a core concept of the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT).

Advantages of Using Sensors

The widespread adoption of sensors is driven by clear, transformative benefits. They provide improved accuracy and precision in measurement compared to manual methods, reducing human error. This enables automation and enhanced efficiency, allowing systems to operate and optimize themselves with minimal human intervention. Furthermore, sensors permit real-time monitoring and control, offering immediate insight into processes and environments for quicker decision-making. Finally, they lead to enhanced safety and predictive capabilities by detecting hazardous conditions (like gas leaks or excessive heat) early and predicting equipment failures before they occur.

Limitations and Challenges of Sensors

Despite their advantages, sensors are not infallible and come with inherent challenges that must be managed. They can exhibit environmental sensitivity, where their readings are affected by factors other than the one being measured, such as temperature affecting a pressure sensor. This leads to a need for regular calibration requirements to maintain accuracy, a process that can be complex and costly, especially for networks of low-cost sensors. All sensors also have a limited lifespan and durability, as sensing elements can degrade over time due to harsh operating conditions like extreme temperatures or chemical exposure. Additionally, their electrical signals can be susceptible to signal noise and interference from other electronic equipment, which can corrupt data if not properly filtered.

Conclusion

In summary, a sensor is a fundamental device that translates physical phenomena into actionable electrical data, serving as the critical interface between our world and the electronic systems that augment it. Their importance in modern technology cannot be overstated, enabling everything from everyday convenience to industrial revolutions. As technology advances, the role of sensors is set to expand further, with trends pointing towards greater miniaturization, intelligence, and integration through the Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI). The future will likely see sensors becoming even more embedded, networked, and capable, driving forward innovations in smart cities, autonomous systems, and personalized healthcare.