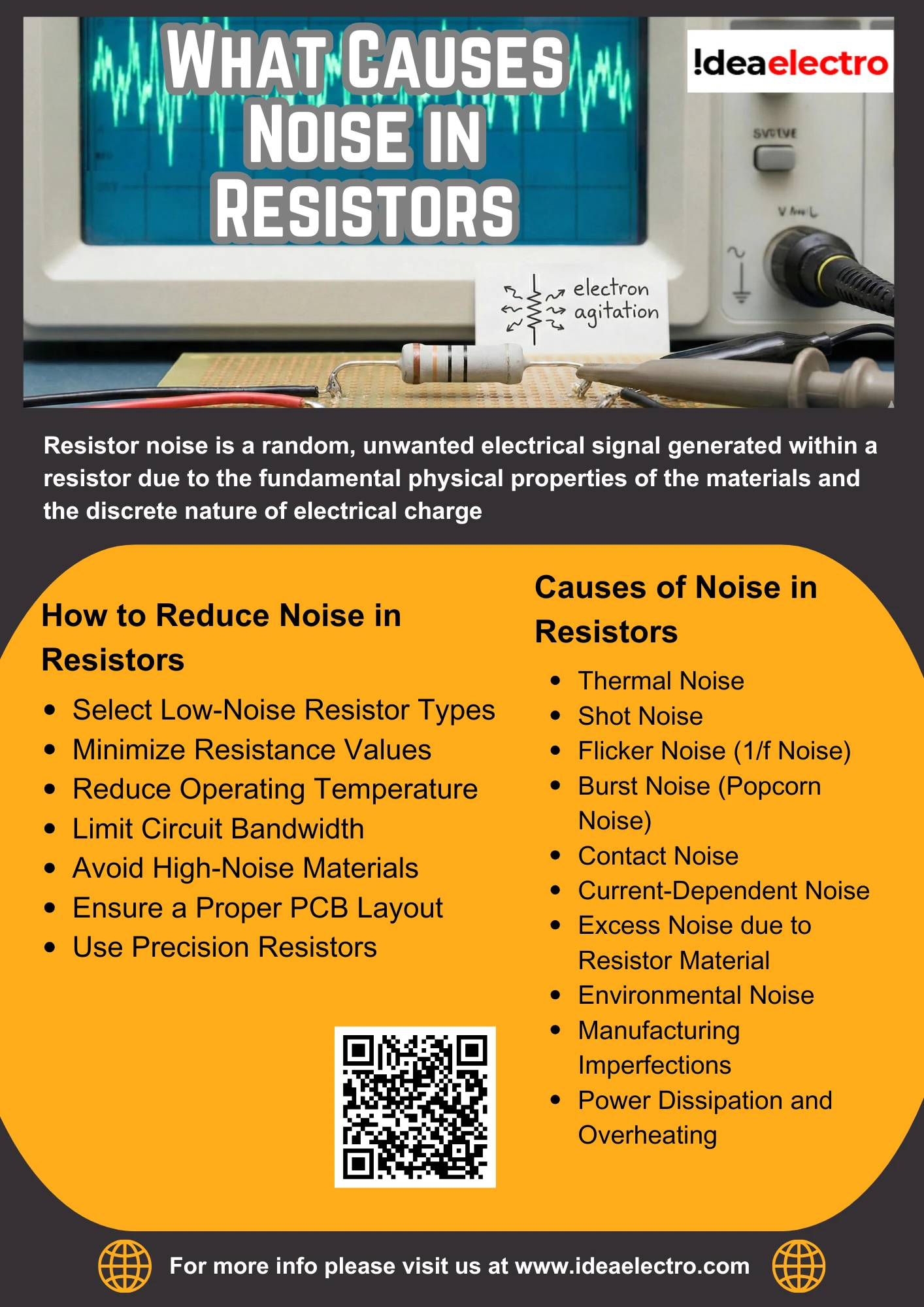

Resistor noise is a random, unwanted electrical signal generated within a resistor due to the fundamental physical properties of the materials and the discrete nature of electrical charge. These microscopic fluctuations are superimposed on the intended signal, creating a background of interference. The generation of this noise is an inherent phenomenon, occurring even in a perfectly manufactured resistor and in the absence of any applied voltage, as the chaotic thermal motion of electrons creates a constantly varying electric potential across the component’s terminals.

Causes of Noise in Resistors

Here are the primary causes of noise in resistors:

- Thermal Noise (Johnson–Nyquist Noise)

Thermal noise is a fundamental, unavoidable phenomenon present in all resistors. It is generated by the random thermal motion of charge carriers (electrons) within the resistive material. This motion creates a small, fluctuating voltage across the resistor’s terminals, even without an applied current. Its magnitude depends solely on the resistor’s temperature, resistance value, and bandwidth. Because it is inherent to all materials, it sets the ultimate signal-to-noise floor for electronic circuits operating at any frequency.

- Shot Noise

Shot noise arises from the discrete nature of electrical current, which is a flow of individual electrons. When current flows, these electrons do not move in a perfectly smooth, continuous stream but arrive at random intervals. This randomness in the timing of charge carriers crossing a potential barrier (like a junction) causes minute fluctuations in the current. It is most significant in semiconductor devices and becomes more pronounced with increasing direct current, appearing as a broadband, white noise.

- Flicker Noise (1/f Noise)

Flicker noise is characterized by its inverse frequency power spectrum, meaning its intensity increases as frequency decreases. It is predominant at low frequencies and is caused by defects and impurities in the semiconductor or resistive material that randomly trap and release charge carriers. This “modulates” the current flow, creating noise. It is a major concern in audio and low-frequency precision applications, as it can introduce a noticeable drift or rumble in the signal.

- Burst Noise (Popcorn Noise)

Burst noise, or popcorn noise, is characterized by sudden, discrete shifts in voltage or current between two or more levels, creating a “pop” or “click” sound in audio outputs. It is caused by the random trapping and release of charge carriers at specific defect sites within a semiconductor, such as crystalline imperfections or metallic impurities. This noise is particularly problematic in precision amplifiers and analog signal processing circuits, where its discrete steps can corrupt sensitive measurements.

- Contact Noise

Contact noise occurs at the interfaces between different materials within a component, such as where a wire lead connects to the resistive element or between granules in a carbon-composition resistor. Fluctuations in the contact resistance, often due to imperfect mechanical connections or oxidation, cause current flow to become erratic. This noise typically exhibits a 1/f-like characteristic and can be minimized by using high-quality components with stable, well-made internal connections.

- Current-Dependent Noise

This category encompasses noise mechanisms whose intensity is directly influenced by the amount of DC current flowing through the resistor. While thermal noise is current-independent, other types like shot noise and excess noise increase with current. In some materials or structures, the flow of current can also induce noise through other effects like local heating, electromigration, or modulation of material properties, leading to a current-dependent noise level beyond the fundamental sources.

- Excess Noise due to Resistor Material

“Excess noise” is a general term for any noise beyond the fundamental thermal noise, and it is heavily dependent on the resistor’s construction. Carbon composition resistors are notoriously noisy due to the granular nature of their material, where current flows unevenly between carbon particles. In contrast, thin-film and wire-wound resistors, made from more homogeneous materials, exhibit significantly lower excess noise, making them preferable for sensitive analog circuits.

- Environmental Noise (Temperature, Humidity, Mechanical Stress)

External environmental factors can induce or modulate noise in resistors. Temperature fluctuations can alter the resistance value, creating low-frequency noise. Humidity can penetrate a resistor’s body, leading to leakage currents and electrochemical noise, especially in non-hermetically sealed types. Mechanical stress, such as vibration or physical strain, can cause microscopic changes in contact points or the resistive element, generating noise known as microphonics, where the component acts like a microphone.

- Manufacturing Imperfections

Imperfections introduced during the manufacturing process are a primary source of excess noise. These include impurities in the base material, microscopic cracks in the substrate, uneven deposition of thin or thick films, and poor quality of internal wire bonds or end-cap connections. These defects create localized sites where current flow becomes unstable, leading to increased flicker and burst noise. Tighter manufacturing controls and higher-quality materials are used to produce premium, low-noise resistors.

- Power Dissipation and Overheating

When a resistor dissipates power, it generates heat. If this heat is not properly managed, it can cause the resistor to overheat. This elevated temperature directly increases the level of thermal noise. Furthermore, excessive heat can cause physical expansion, degrade internal contacts, or accelerate electrochemical processes, all of which contribute to additional excess noise. Ensuring a resistor operates within its rated power and temperature limits is crucial for minimizing noise.

Comparison of Noise Performance by Resistor Type

| Resistor Type | Noise Level | Typical Use Case |

| Metal Foil | Very Low | Precision instrumentation, high-end audio, aerospace |

| Wirewound | Very Low | High-power applications, current sensing (but can be inductive) |

| Thin Film | Low | Precision low-noise circuits, medical devices, amplifiers |

| Metal Film | Low to Medium | General-purpose electronics, where low cost and good performance are needed |

| Thick Film | Medium to High | Consumer electronics, cost-sensitive applications |

| Carbon Composition | High | Legacy or general-purpose use; avoided in low-noise designs |

How to Reduce Noise in Resistors

- Select Low-Noise Resistor Types: Prioritize metal film, thin film, or wirewound resistors for critical signal path applications, especially in the input stages of amplifiers where noise is amplified the most.

- Minimize Resistance Values: Use the lowest practical resistance values in your circuit design, as this directly reduces the generated thermal noise voltage.

- Reduce Operating Temperature: Cooling the input stages of a circuit can be a very effective way to lower thermal noise, though this is often reserved for highly specialized equipment.

- Limit Circuit Bandwidth: Since total noise is proportional to bandwidth, restrict the system’s bandwidth to only what is necessary for the signal. This can be achieved with filters that block out-of-band noise.

- Avoid High-Noise Materials: Steer clear of carbon composition and generic thick film resistors in sensitive, low-signal applications.

- Ensure a Proper PCB Layout: Good practices, such as using short traces, solid grounding, and shielding sensitive nodes, can prevent noise from being picked up or injected into the circuit.

- Use Precision Resistors for Sensitive Analog Signals: In applications like sensor signal conditioning or medical instrumentation, the improved stability and lower noise of precision resistors are worth the additional cost.

When Does Resistor Noise Become a Real Problem?

Resistor noise transitions from a theoretical concern to a practical problem in applications that involve amplifying very weak signals or require high signal integrity. It is a critical limiting factor in the design of high-gain amplifiers, where the input-referred noise determines the smallest detectable signal. In audio equipment, such as microphone preamplifiers and high-fidelity systems, resistor noise manifests as a persistent hiss, degrading the listening experience. Furthermore, it compromises the accuracy of low-frequency measurement systems, medical diagnostic devices like ECG and EEG machines, and any circuitry involved in processing sensor data from thermocouples, strain gauges, or photodiodes.