In the intricate world of electronics, countless components work in harmony to bring functionality to the devices we use every day. Among these, the resistor stands out as one of the most fundamental and ubiquitous passive components. A resistor is a two-terminal electronic element specifically designed to implement electrical resistance as a circuit element . These components are absolutely indispensable; they are found in virtually every electrical network and electronic circuit, from the simplest children’s toy to the most advanced supercomputer . Without resistors, it would be impossible to precisely control the flow of electricity, rendering most modern electronic circuits non-functional. Their role may seem simple, but their proper application is a cornerstone of electronic design and a critical first topic for anyone venturing into the field of electrical engineering or electronics.

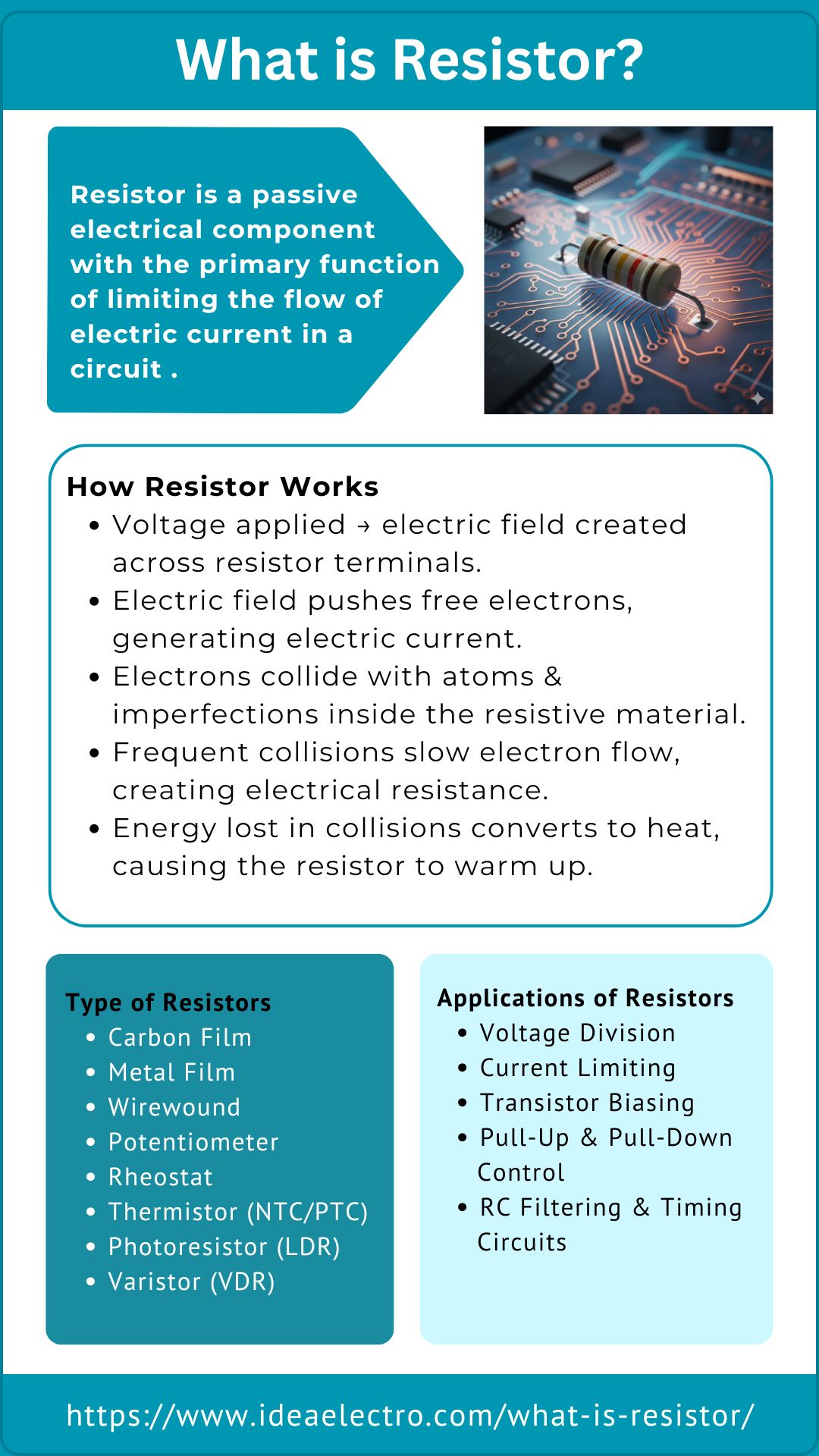

Definition and Basic Concept of Resistor

At its core, a resistor is a passive electrical component with the primary function of limiting the flow of electric current in a circuit . When we speak of passive components, we refer to those that do not generate or amplify power but instead absorb energy, which resistors typically dissipate as heat. The core property of a resistor is its resistance, which quantifies how strongly the material opposes the movement of electrons. The official unit of resistance is the ohm (Ω), named after the German physicist Georg Simon Ohm . One ohm is defined as the resistance that allows one ampere of current to flow when one volt of electrical force is applied across it.

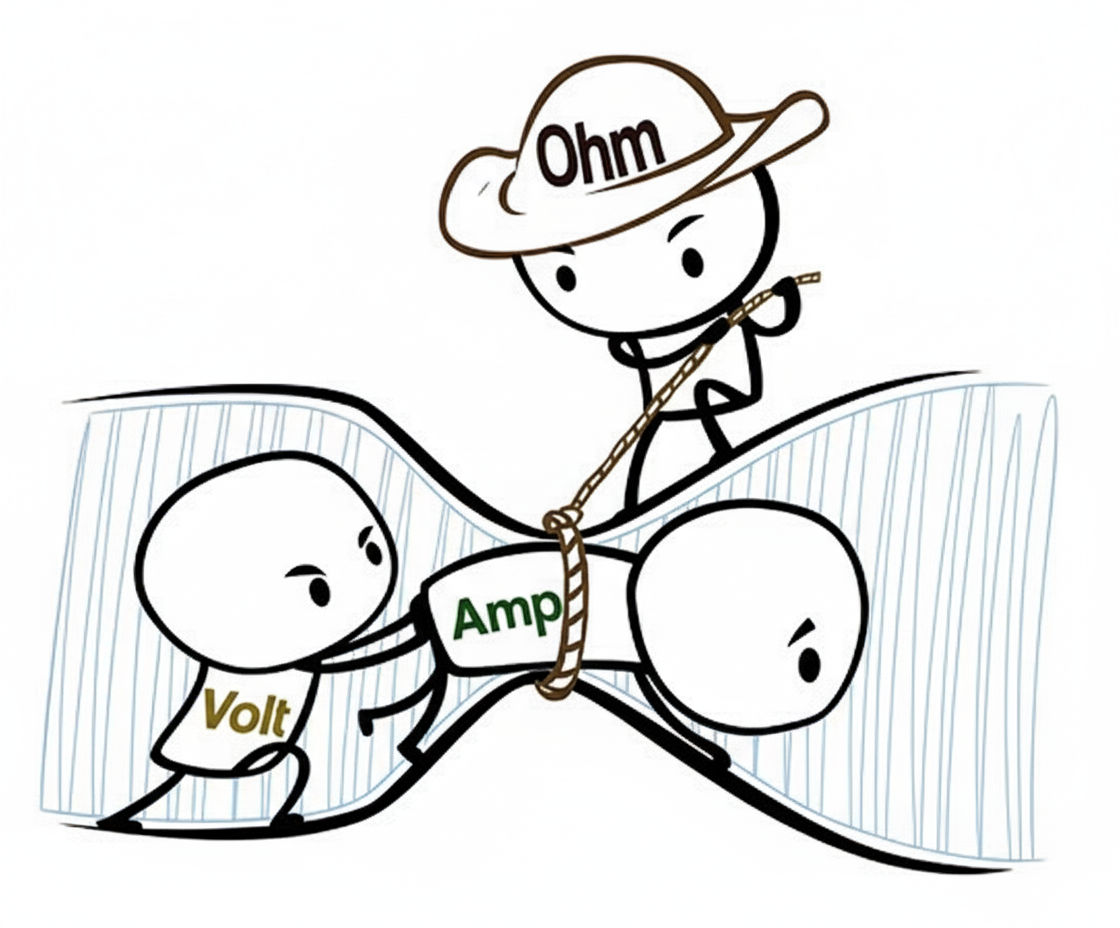

The relationship between voltage, current, and resistance is elegantly captured by Ohm’s Law, a fundamental principle in electrical engineering. This law states that the electric current flowing through a conductor between two points is directly proportional to the voltage across the two points and inversely proportional to the resistance between them . This relationship is most commonly expressed by the formula V=I×RV=I×R, where VV represents voltage in volts, II represents current in amperes, and RR represents resistance in ohms . By providing a predictable and controllable amount of opposition to current, a resistor allows circuit designers to set specific conditions necessary for other components to operate correctly and safely.

How a Resistor Works

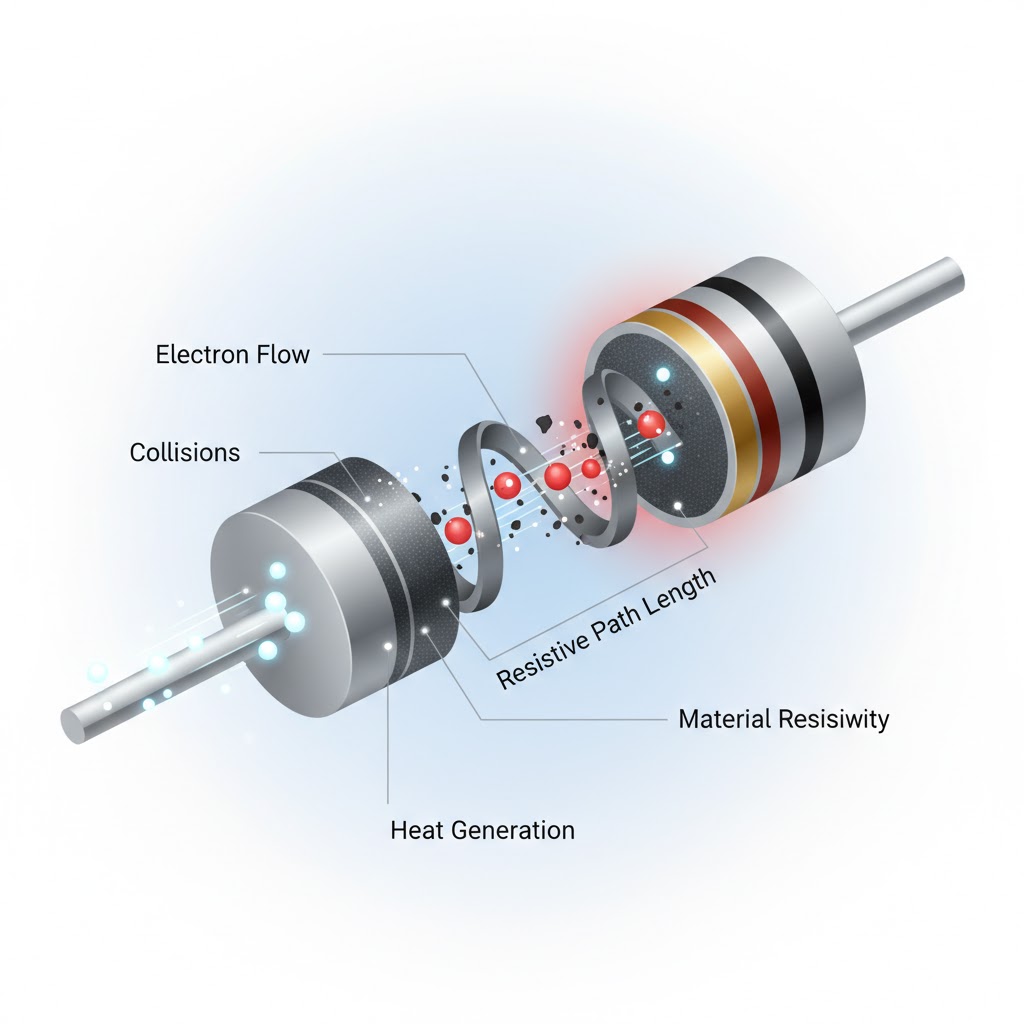

The operation of a resistor can be understood by examining the behavior of electrons as they move through a conductive material. When a voltage is applied across a resistor’s terminals, it creates an electric field that forces free electrons to flow, constituting an electric current. However, the resistive material is not a perfect conductor; it is filled with atoms and imperfections that the electrons frequently collide with during their journey . It is these countless collisions that impede the orderly flow of electrons, creating the phenomenon we know as electrical resistance. The energy lost from each collision is converted from electrical energy into thermal energy, or heat, which is why resistors often become warm during operation.

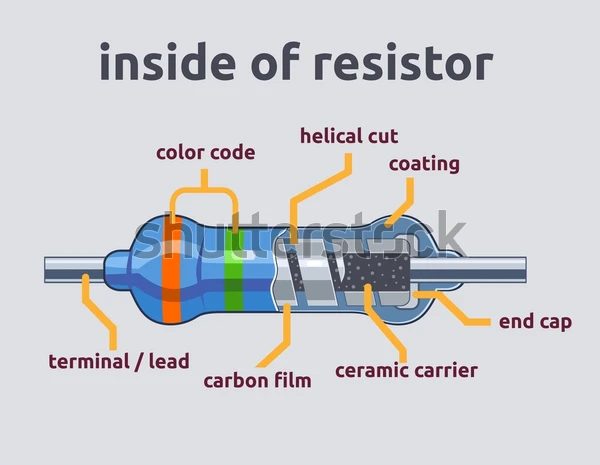

The amount of resistance a component provides is not arbitrary; it depends on several physical factors. These include the resistivity of the material itself (an intrinsic property), the length of the conductive path (longer paths create higher resistance), and the cross-sectional area (thicker paths create lower resistance) . In practice, most fixed resistors are constructed using materials like carbon, metal, or metal oxide, which have naturally high resistivity. For instance, in carbon film resistors, a thin carbon layer is deposited on an insulating substrate, and a precise spiral cut is made to increase the length and narrow the path of the current, thereby increasing the resistance . This process of energy conversion—from electrical energy to heat—is the fundamental mechanism by which resistors perform their current-limiting function.

Ohm’s Law and Relationship Between Voltage, Current, and Resistance

Ohm’s Law provides the essential mathematical framework for understanding and predicting the behavior of electrical circuits. The formula V=I×RV=I×R is not just an equation but a profound statement about the relationship between three interdependent quantities . It tells us that for a given resistance, the current in a circuit is directly proportional to the applied voltage. Conversely, for a fixed voltage, the current is inversely proportional to the resistance; doubling the resistance will halve the current, and vice-versa . This inverse relationship between current and resistance is a key design tool for engineers.

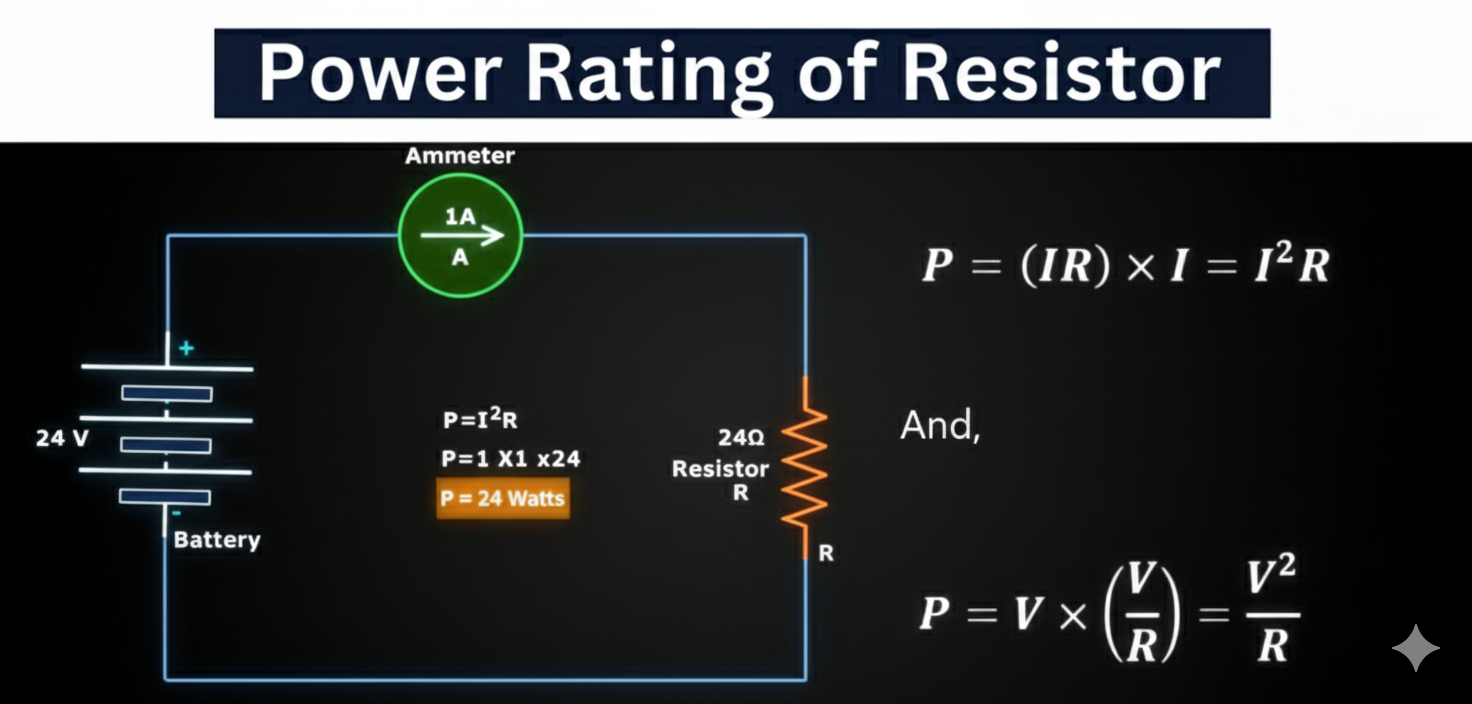

To illustrate with a practical example, consider a simple circuit with a 9-volt battery and a resistor. If a resistor with a value of 3 ohms (Ω) is used, the current flowing through the circuit can be calculated as I=V/RI=V/R, which is 9V/3Ω=39V/3Ω=3 Amperes (A) . If we were to replace the 3Ω resistor with a 9Ω resistor instead, the new current would be 9V/9Ω=19V/9Ω=1 Ampere. This simple calculation demonstrates how a designer can precisely control current in a circuit by selecting an appropriate resistor value. Furthermore, Ohm’s Law can be combined with the power formula P=V×IP=V×I to calculate power dissipation . Substituting Ohm’s Law into the power equation gives us P=I2×RP=I2×R and P=V2/RP=V2/R, which are crucial for ensuring a resistor does not overheat .

Types of Resistors

The diverse needs of electronic circuits have led to the development of a wide variety of resistor types, each with unique characteristics, construction methods, and ideal application areas. They can be broadly categorized into fixed resistors, variable resistors, and special-purpose resistors.

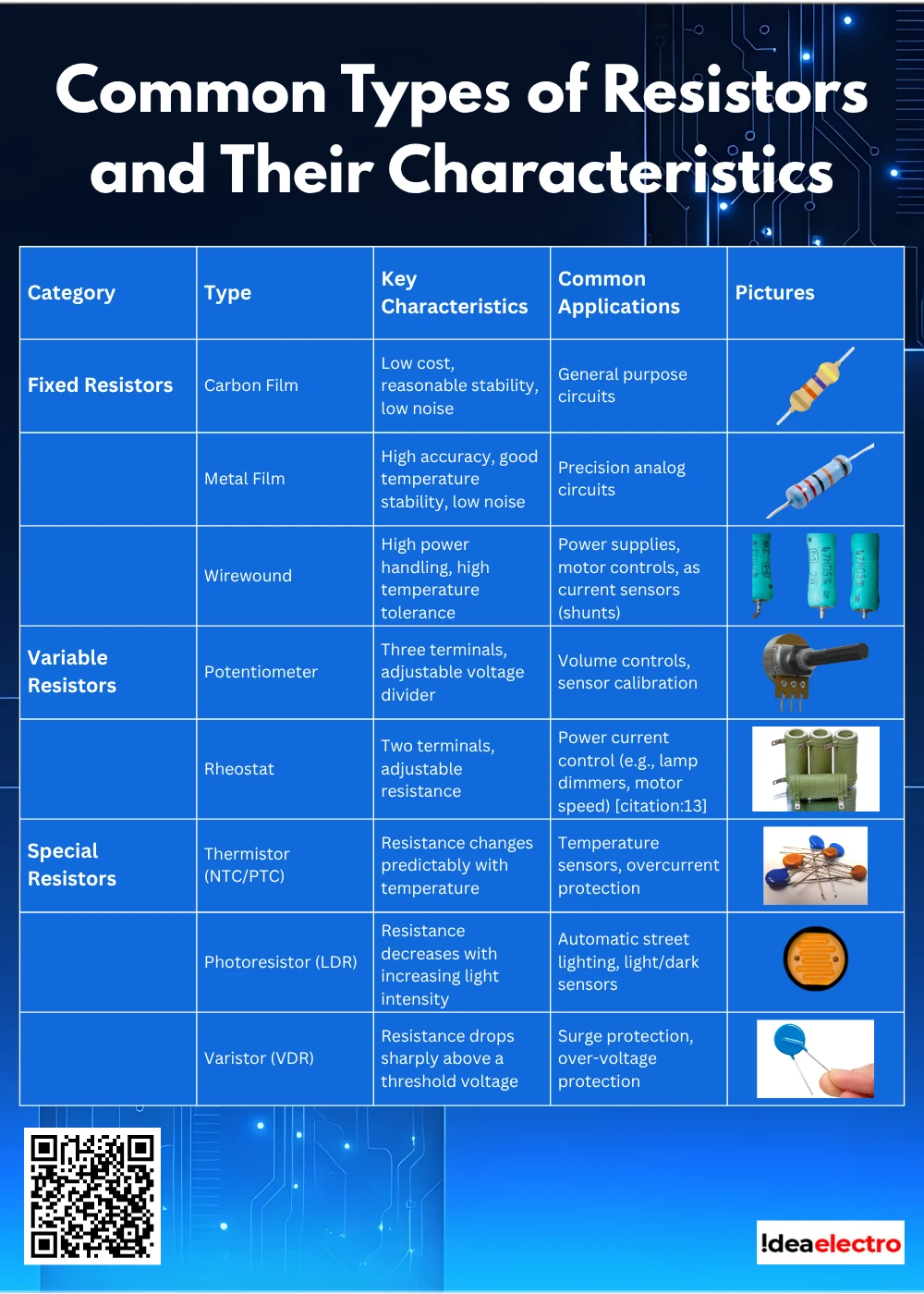

Table: Common Types of Resistors and Their Characteristics

| Category | Type | Key Characteristics | Common Applications | |

| Fixed Resistors | Carbon Film | Low cost, reasonable stability, low noise | General purpose circuits | |

| Metal Film | High accuracy, good temperature stability, low noise | Precision analog circuits | ||

| Wirewound | High power handling, high temperature tolerance | Power supplies, motor controls, as current sensors (shunts) | ||

| Variable Resistors | Potentiometer | Three terminals, adjustable voltage divider | Volume controls, sensor calibration | |

| Rheostat | Two terminals, adjustable resistance | Power current control (e.g., lamp dimmers, motor speed) [citation:13] | ||

| Special Resistors | Thermistor (NTC/PTC) | Resistance changes predictably with temperature | Temperature sensors, overcurrent protection | |

| Photoresistor (LDR) | Resistance decreases with increasing light intensity | Automatic street lighting, light/dark sensors | ||

| Varistor (VDR) | Resistance drops sharply above a threshold voltage | Surge protection, over-voltage protection |

Fixed resistors are the most common type, designed to have a single, unchangeable resistance value . Variable resistors, on the other hand, allow users to manually adjust their resistance. When configured as a three-terminal voltage divider, they are called potentiometers, commonly found in volume controls. When used as a two-terminal variable resistance, they are termed rheostats . Finally, special-purpose resistors have properties that change in response to environmental stimuli. Thermistors change resistance with temperature, photoresistors (LDRs) change with light, and varistors change with voltage, making them invaluable as sensors and protective devices .

Resistor Color Code and Identification

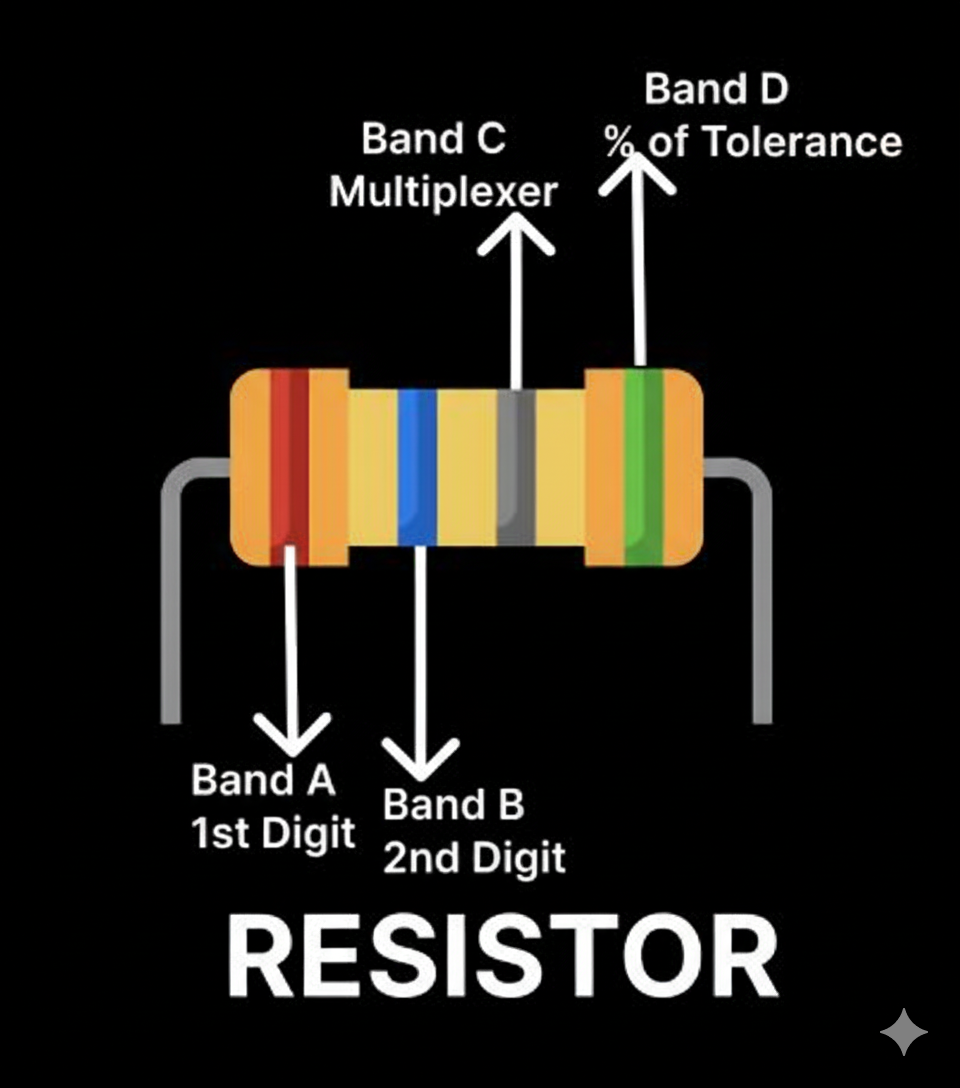

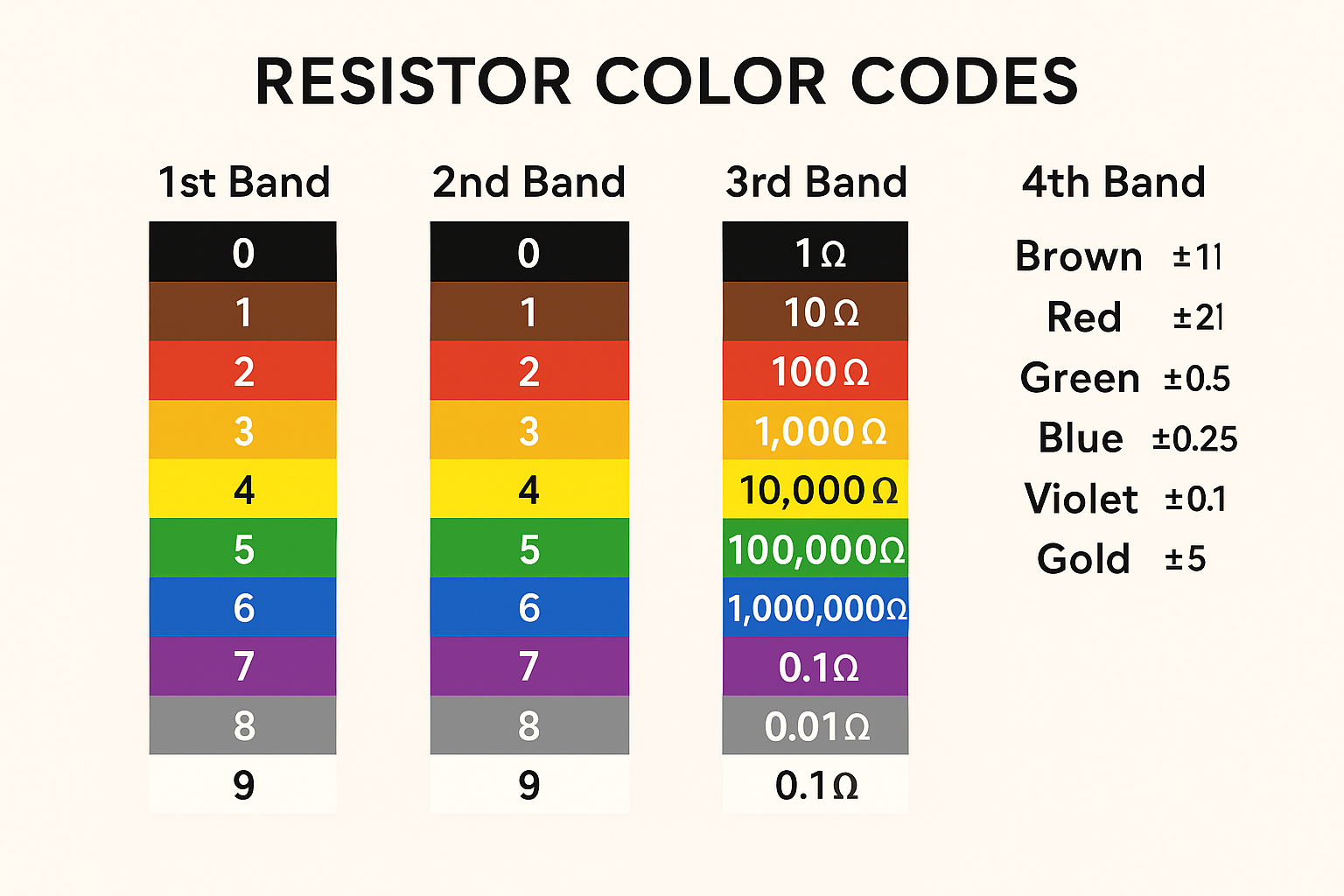

To identify the resistance value and tolerance of small axial-lead resistors, a universal color code system is used. This system was developed in the early 20th century because printing tiny, legible numbers on the small component body was not feasible with the technology of the time . The most common system is the 4-band code, though 5-band and 6-band codes also exist for more precise resistors.

In the 4-band system, the first two bands represent the first two significant digits of the resistance value. The third band is the multiplier, which indicates the power of ten by which the significant digits are multiplied. The fourth band indicates the tolerance, which is the percentage of uncertainty in the resistance value . For example, consider a resistor with band colors yellow, violet, red, and gold. Yellow is 4, violet is 7, so the significant digits are 47. The red multiplier is 102102, or 100. Therefore, the value is 47×100=470047×100=4700 ohms, or 4.7 kΩ. The gold band indicates a ±5% tolerance . For Surface Mount Device (SMD) resistors, which are too small for color bands, a numerical code is used instead. For instance, a marking of “331” means 33×101=33033×101=330 Ω .

Applications of Resistors in Electronic Circuits

Resistors are the workhorses of electronic circuits, performing a vast array of critical functions that ensure proper operation, stability, and safety. One of their most fundamental applications is in voltage division. By connecting two resistors in series, a designer can create a voltage divider circuit that produces a specific, lower voltage from a higher source voltage. This is crucial for providing appropriate bias voltages to different parts of a circuit or for scaling down voltages for measurement by microcontrollers .

Another vital application is current limiting. A resistor placed in series with a sensitive component, like a Light Emitting Diode (LED), will limit the amount of current that can flow, preventing the component from being destroyed by excessive current . This principle is also used in the bleeder resistors found in power supplies, which safely discharge capacitors after the equipment is turned off. Resistors are also essential in biasing transistors, setting their DC operating point to ensure they function correctly in amplification circuits . In digital electronics, pull-up and pull-down resistors are used to ensure that microcontroller input pins settle at a defined logic level (high or low) when no active input signal is present, preventing erratic behavior caused by floating inputs . Finally, when combined with capacitors, resistors form RC (resistor-capacitor) networks that can filter out unwanted noise, shape signal waveforms, and create timing circuits for oscillators and clock signals .

Power Rating and Tolerance

Beyond the resistance value itself, two of the most critical specifications for any resistor are its power rating and its tolerance. The power rating, measured in watts (W), indicates the maximum amount of power the resistor can dissipate continuously without suffering permanent damage or significant degradation . Exceeding this rating causes excessive heat buildup, which can lead to the resistor burning out, cracking, or even catching fire . Common general-purpose resistors have power ratings of 1/4 watt or 1/2 watt, while specialized power resistors can handle tens, hundreds, or even thousands of watts, often requiring heatsinks to do so .

Tolerance is a measure of the manufacturing precision of the resistor. It expresses how close the resistor’s actual resistance is to its stated nominal value, expressed as a percentage . For instance, a 1,000 Ω resistor with a ±5% tolerance could have an actual resistance anywhere between 950 Ω and 1,050 Ω. In a typical circuit, a 5% tolerance is acceptable, but in precision applications like medical devices or high-quality audio amplifiers, resistors with 1%, 0.1%, or even tighter tolerances are required . The tolerance is often indicated by the last band in the color code, with gold representing ±5% and silver representing ±10% .

How to Choose the Right Resistor

Selecting the appropriate resistor for a given circuit involves considering several key factors to ensure both performance and reliability. The most obvious parameter is the required resistance value in ohms, which is typically calculated using Ohm’s Law based on the desired current or voltage drop in the circuit . Online Ohm’s Law calculators can simplify these calculations .

Next, the power rating must be carefully considered. A good rule of thumb is to choose a resistor with a power rating at least 50% to 100% higher than the maximum power it is expected to dissipate in the circuit. This provides a safety margin, especially in environments where ambient temperature might be high . The required tolerance must also be selected; for most non-critical applications, 5% is sufficient, but precision analog circuits may require 1% or better . Finally, the operating environment must be considered. Will the resistor be subjected to high temperatures, humidity, or mechanical vibration? In such cases, a more robust resistor type, like a wirewound or metal oxide film resistor, may be necessary instead of a standard carbon film type .

Common Problems and Failures of Resistors

Despite being simple and robust, resistors are not immune to failure. Understanding common failure modes is essential for troubleshooting electronic equipment. The most frequent failure is overheating and burnout, which occurs when the resistor is subjected to a current or voltage exceeding its rated capacity, causing it to char, crack, or melt . This often manifests as visible discoloration or burn marks on the component and the circuit board.

Another common issue is the open circuit failure, where the resistor breaks internally, completely interrupting the flow of current . This can be caused by physical stress, a severe electrical surge, or manufacturing defects. Conversely, though rarer, short circuit failures can occur where the resistance drops to nearly zero, causing excessive current flow that can damage other parts of the circuit . Resistors can also suffer from resistance drift, where their value slowly changes over time due to aging or prolonged exposure to high temperatures . The primary tool for diagnosing resistor failure is a multimeter, used to measure the component’s resistance. A significant deviation from the marked value (outside the tolerance range) or an infinite reading (open circuit) indicates a faulty resistor that needs replacement .

Conclusion

From this comprehensive exploration, it is clear that the resistor, though humble in its function, is an irreplaceable pillar of electronic engineering. Its ability to precisely control current, divide voltages, dissipate power, and set operating conditions makes it the cornerstone upon which reliable and predictable circuits are built. A firm grasp of Ohm’s Law, the various resistor types, their identification methods, and their practical applications is fundamental for anyone involved in electronics, from hobbyists to professional engineers. While more complex components often capture the imagination, it is the simple resistor that provides the stability and control necessary for all electronic systems to function correctly. Mastering this essential component is, without a doubt, the first step toward true proficiency in the art and science of circuit design.